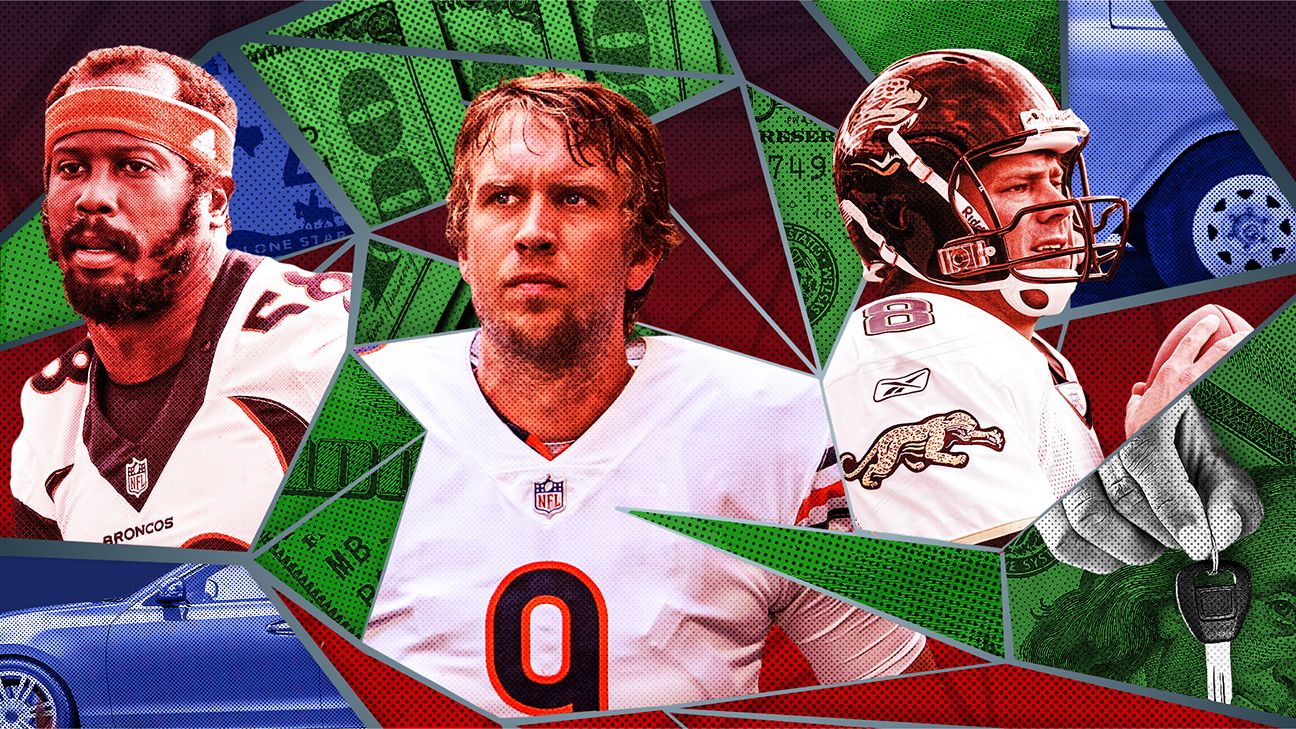

INVESTMENTS FROM AT least 15 current and former NFL players, including Von Miller, Nick Foles and Mark Brunell, were used in a complex investment program designed to profit at the expense of low-income borrowers, according to civil and bankruptcy court documents obtained by ESPN.

The players invested in a now-defunct company that funded a separate business targeting Texans with troubled credit ratings who needed quick cash and would put up their cars as collateral on loans averaging $1,000. Because of fees and interest in excess of 300%, borrowers would agree to pay hundreds of additional dollars to repay the loans. The so-called auto title loans are legal in Texas but prohibited in many states because they prey on people who lack access to traditional banking sources.

Yet it turned out to be a bad deal not just for desperate borrowers. The orchestrator of the investment, longtime financial adviser Joseph “Joey” Feste, claimed in court filings that the venture was in default of promises to pay investors some $40 million. It’s not known how much the athletes lost, although millions linked to NFL players helped fund the title loans, according to documents Feste filed. Feste, owner of KM Capital Management, an Austin, Texas-based private wealth management firm that caters to athletes, ultimately lost his status as an NFL Players Association-registered financial adviser, in part for failing to disclose to the union the civil litigation related to the title loans.

Today, Feste still acts as a financial adviser to NFL players, though without the union’s official blessing, with a client list featuring recently retired Drew Brees and current talents such as Patrick Mahomes and Tua Tagovailoa.

Neither the players who invested nor Feste were charged with any crimes, though ESPN has learned Feste was the subject of a whistleblower complaint filed in late 2019 with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Feste declined multiple interview requests for this story, and his attorneys declined to answer specific questions related to the investments which were part of a bankruptcy proceeding that ended last October.

“My client’s reaction is that this is an old story about an old investment that has been vetted by several regulatory entities charged with the responsibility of doing so,” said attorney Andrew Kim, who represents Feste. “It was completely cleared of any problems. It was a totally legal business.”

Kim noted: “And the court documents describe it all. It is all there in the court documents.”

The players’ involvement in a business that targeted low-income borrowers puts them at odds with recent statements and actions by the league and the NFLPA on issues of inequality and social and racial injustice. “The Players Coalition has led the efforts of players and clubs to engage with leaders at all levels of government … on issues like bail and criminal justice reform; [to] promote education reform and economic opportunity in disadvantaged communities,” among other efforts, the league and union said in a joint statement last September.

When contacted by ESPN, some players said they did not know how their money had been invested or whether they made or lost money. “I am not sure of the particulars,” said former NFL backup quarterback Ken Dorsey, now the Buffalo Bills’ quarterbacks coach. “I am not as good as I hope to be with some of this stuff. Part of my problem is I don’t understand a lot of it. I kind of trust the people.”

Other current or former players, including Foles and Miller, did not respond to questions from ESPN or declined to discuss their investments.

THE DETAILS OF the title loan investment involving the athletes have largely been buried in nondescript civil and bankruptcy case files in the federal court system. Though the file has been publicly accessible for years, the athlete connections have not been made public prior to ESPN investigating the case.

In 2011, Feste founded Storehouse Lending LLC, which had a purpose of funding title loans offered by a partner company called KJC Auto Title Loan, the court documents show. Storehouse funded KJC Auto, in part, by getting clients of Feste’s KM Capital and other investors to buy high-yield promissory notes — financial promises that weren’t registered with federal or state regulators. The players’ notes ranged from less than $10,000 to more than $500,000, court documents show. Storehouse then partnered with KJC Auto to invest the raised cash into title loans, with Storehouse appearing on titles as the lien holder.

From 2011 to 2014, at least $6 million linked to NFL players funded KJC Auto’s title loans, according to the documents filed by Feste. The players and other Feste clients were typically paid a return of between 9% and 20% on their investments that funded the title loans, the documents say. Records show Storehouse typically received returns of up to 22% on capital it provided to KJC Auto.

At the other end of the arrangement were borrowers who signed up for loans stacked with fees and charges, some with annual percentage rates in excess of 300%. For example, in 2013, an Austin-area woman put up her 2002 Mercury Mountaineer as collateral to borrow $1,039.99. With a $2,426.64 finance charge, she agreed to pay $3,466.63 back to KJC in principal and interest over 17 payments, according to court documents. It’s unclear from the documents if the woman was able to repay the loan.

Such loans have come under increasing scrutiny for furthering the wealth gap by targeting people in desperate financial straits. A 2019 survey by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation found minorities made up a disproportionate number of auto title loan consumers in Texas. In Texas, one in five borrowers are unable to repay the loans and get their cars repossessed, according to Texas Appleseed, a nonprofit that seeks social and economic justice in the state.

“It was, in my mind, criminal because the ones who were taking out the loans were generally poor people who could least afford to repay, and who were not necessarily financially savvy,” said Marilyn Garner, the trustee who oversaw KJC Auto’s eventual bankruptcy. “And the problem is, it is not illegal.”

The Storehouse arrangement started to collapse in 2014, after Texas regulators began an investigation into KJC Auto. Investigators uncovered numerous violations, including that the company was evading established interest rate limits by paying additional fees to Storehouse. The state audit also found loans exceeding laws limiting their duration to 180 days, citing some that extended 18 months.

The investigation led KJC Auto to shutter stores across Texas. Feste’s Storehouse promptly filed a civil lawsuit against KJC Auto, claiming, among other allegations, breach of contract and fraud. KJC Auto responded by filing for Chapter 7 liquidation bankruptcy.

KJC Auto chief financial officer Ken Phillips and chief executive officer Clifton Morris III declined comment.

The bankruptcy case dragged on for nearly five years. In 2017, the bankruptcy trustee awarded Storehouse KJC’s files and loan documents as a way to recoup some of its losses. Rather than attempt to repossess vehicles, Storehouse sold the liens to 13,000 auto title loans to a Texas collection firm for $75,000, according to documents.

In civil and bankruptcy court documents, Feste said Storehouse was at the time in default of about 74 promissory notes, totaling $40 million. The final bankruptcy report issued this past October reveals Storehouse Lending asserted a claim of $37,592,043 — all of which was allowed by bankruptcy trustee Garner. However, the report indicates the trustee was able to pay Storehouse only $431,808 — about 1 percent of its claim.

Kim declined to discuss the amount awarded by the trustee or whether the athlete investors lost any of their principal investments. “OK, it’s a monetary difference,” Kim said. “So, a business that didn’t work out. I just don’t see where the story is.” Feste formally dissolved Storehouse in 2018.

Garner told ESPN she was unaware that professional athletes had invested in the title loan venture but said not all investors could be made whole in the case.

“There was not enough money ever collected to repay their claim in full,” Garner said. “So, it was a loss all the way around. They got what they got from the estate and that was it. Whatever else may have been owed to them based on their documentation was just a general unsecured claim, and was not paid.”

FESTE, 56, is the senior managing partner as well as chief compliance officer of KM Capital Management, which recently disclosed in U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission documents having $245 million in assets under its control. “We pay bills, we negotiate leases, we buy cars and insurance, we touch nearly every part of their financial lives so that nothing falls through the cracks,” he said in an interview with an entrepreneurship website last year. His son, Joey Feste Jr., is a vice president at the firm.

A handful of the elder Feste’s NFL clients either grew up or played college football in Texas, where Feste graduated from the University of Texas. Feste is also the co-founder and senior leader of Kingdom Life San Antonio, a Christian congregation, alongside his wife, Kelley, and has “strived to base his business on strong Christian values,” according to his personal blog.

During an hour-plus Sunday sermon on March 21, Feste described himself as a “recovering control freak.” Mixed in with his message, titled “De-Church-ifying the Church,” was a reference to his day job as financial adviser to the stars.

“People have been feeling used outside our culture,” Feste said. “I manage some of the highest-profile players in the world. And I build relationships with them. And my hope and prayer is, if they are even watching this, that they know that they can associate me with the way, because I love them in spite of. I love them because of. And I love them, period. And each one of my clients are in different levels of maturity in their life.”

ESPN has attempted since mid-March to speak with Feste. An initial phone message was returned by two of his attorneys, who said he was unavailable due to a health issue. At the last minute, Feste was not on a scheduled March 24 call because it was “not conducive to a recuperative process,” said Andrew Kim, one of the attorneys. The attorneys declined to address questions about the title loan investment and whether investors, including NFL players, lost any of their investments in Storehouse. They noted that Feste was a plaintiff and not a defendant in civil lawsuits around the investments.

“What’s in the court documents is what we’re providing in terms of answers,” said attorney Rebecca Riley.

IN ADDITION TO Foles, Miller and Brunell, investors in the Storehouse-funded loans included former Tampa Bay Buccaneers linebacker and Hall of Famer Derrick Brooks, via his limited liability company, and Kansas City Chiefs all-time rushing leader Jamaal Charles. Former Green Bay quarterback Matt Flynn and former New England Patriots running back Shane Vereen also were listed as investors, as was Rice assistant coach Marques Tuiasosopo.

Other since-retired players listed in documents as Storehouse noteholders included: running back Justin Forsett, linebacker Sean Weatherspoon, defensive end Renaldo Wynn and wide receiver Damian Williams.

Brunell, the former Jaguars quarterback, had the largest investment listed among the named athletes, according to documents filed by Feste, with three accounts totaling at least $1.9 million. Flynn contributed about $1.5 million, while Miller invested about $700,000.

Multiple messages left for Miller’s agent, Joby Branion of Vanguard Sports Group, went unanswered. California-based attorney Kim, along with representing Feste, is employed as Vanguard’s general counsel. He also previously represented Miller in legal proceedings. Players reached for comment typically said they remain loyal to Feste, but most declined to comment on the title loan investment or say if they lost money. Some never responded to messages left by ESPN.

Matt Flynn said he hooked up with Feste after leading LSU to a national title in the 2007 college season. In the NFL, Flynn backed up Aaron Rodgers in Green Bay and later signed a reported three-year, $26 million free-agent deal with the Seattle Seahawks. Flynn made at least 10 investments in Storehouse over about two years, according to documents filed by Feste.

In an interview, Flynn described Feste as doing a “great job” for him and being up front. He said he invested less than $1 million in the Storehouse investment, but declined to say how much. Asked if he lost money on the deal, Flynn said, “Well, I’d have to go back and look at everything. That’s all I know right now.”

Asked about profiting from a business that has come under scrutiny for preying upon low-income communities, Flynn said, “Yeah, again, I don’t really know enough about it. When you’re playing, you don’t take a deep dive into everything where your money is at. But you understand everything from a pretty decent perspective.”

Dorsey, who led the University of Miami to the 2001 national championship, also said he met Feste as he entered the NFL. Documents show he had two investments totaling $100,000. Dorsey recalled knowing the Storehouse deal had troubles resulting in a lawsuit, but not much else. As for if he and the players got their money back, he said, “I just don’t want to get into it.”

Brooks, who documents show invested at least $75,000 through his limited liability company, Hit 55 Ventures, told ESPN his dealings with Storehouse went through Ben Renzo, a California attorney who is among the founders of Argent Pictures, a film company that lists Brooks and other athletes as partners. Renzo, who wrote “Hall of Fame: How to Manage Financial Success as a Professional Athlete,” was listed as receiving finder’s fees for investments by Brooks and former NFL lineman Eric Steinbach, according to documents.

Brooks said he got his money back from the Storehouse investment. “All of my dealings with the company was through [Ben Renzo],” he said before cutting off the interview. “So, again, I didn’t have much interaction with that. He’s more the guy that can give you more information than I can.” Neither Renzo nor Steinbach responded to multiple messages seeking comment.

Nick Foles’ agent, Justin Schulman, said the Super Bowl-winning quarterback had “no interest in talking about it.”

Pete Roe, who is himself a financial adviser, told ESPN he was working with former NFL defensive end Demetric Evans when Feste pitched the Storehouse deal. Roe said he cautioned Evans against buying in. “My partner and myself at the time looked at it, and our comment back to him [Demetric] at the time was ethically, if for no other reason, it doesn’t look good or feel good,” Roe told ESPN.

But records show Evans, who played for Dallas, Washington and San Francisco, invested at least $46,000 in two installments. While searching files to confirm Evans’ commitment, Roe said he found an additional promissory note Evans had with Storehouse Lending from 2011 for $50,000. Evans told ESPN he has no recollection of the deal and said Roe might have invested on his behalf. Roe declined to comment further without discussing with Evans. When contacted earlier in February, Evans declined to specifically address whether he lost money, saying, “I can’t speak on it, man.”

When reached by ESPN, Brunell, who was recently named the quarterbacks coach for the Detroit Lions, declined comment, repeating, “I am not talking about that.”

At least one player involved in the Storehouse investments, Brooks, received the NFL Walter Payton Man of the Year Award, which recognizes players for their off-field philanthropy and community impact. Miller was a nominee for the award in 2018.

Even the suggestion of players being unfamiliar with the investment and blindly trusting Feste is troubling to some. “This is targeting the most desperate people and setting them up to fail,” said Ann Baddour, a project director with Texas Appleseed and a former member of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau’s Consumer Advisory Board. “I could see perhaps [investors] could argue they don’t know. Then, I think that is a very low level of accountability.”

UNLIKE ITS RULES for player agents, who are required to be NFLPA-approved before representing players, the union allows players to employ any financial adviser they want, even if that adviser is not registered with the union. During an annual review of registered financial advisers in May 2017, NFLPA investigators discovered that Feste hadn’t disclosed the civil lawsuit he filed on behalf of Storehouse against KJC Auto, among other violations of the union’s code of conduct.

The union ended up revoking Feste’s registration partly because of his failure to disclose the matter, according to a letter obtained by ESPN that NFLPA associate general counsel Ned Ehrlich sent to Feste. Feste initially admitted the failure to disclose but argued the lapse was minor and not worthy of suspension, a union official who asked not to be named told ESPN. When the NFLPA sought additional investigation into the Storehouse investment, Feste did not produce documents or travel for an interview, the official said.

Feste’s lawyer sent the union a draft lawsuit that claimed the suspension damaged his business. The union offered Feste $10,000 to end the matter, but the official said Feste never responded to the offer and never filed the lawsuit. Interviewed on a Christian podcast last year, Feste discussed crisis in his life and opened up about his battle with the NFLPA without directly naming the union. “I was in a battle with them,” Feste said. “It was one of those things — in my business reputation is everything. I built a reputation of trust with athletes and clients for 33 years. And spotless record. And this group was coming after me with nothing. It was affecting me and my business.

“My clients were my biggest advocates against the very organization that was saying things about me, which they were a part of. So, all that started moving into play. And watching God move in that — it was just supernatural.”

The union official said Feste also was skirting NFLPA guidelines, including one that requires promissory notes and other alternative investments come with a series of disclosures in advance of the investment. Feste might be required to shed more light on the investment going forward. According to an attorney who spoke to ESPN only on the condition of anonymity, Feste is the subject of a whistleblower complaint filed in late 2019 with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, which accuses Feste of committing “multiple securities violations and fraud on his clients” in connection to Storehouse Lending. The complaint further alleges Feste failed to register more than $40 million of high-yield promissory notes, failed to disclose he was the owner of Storehouse and was therefore “materially conflicted” in the sale of the notes, and likened Feste’s actions to a Ponzi scheme, accusing him of having “fraudulently used payments due to some Promissory Note holders to pay off other ‘VIP CLIENT’ Promissory Note Holders.”

The attorney said his law practice filed the original complaint on behalf of a whistleblower who didn’t reveal his identity to the SEC. Realizing investigators wouldn’t have a means of following up with the whistleblower if they sought additional information, the attorney said his firm filed a duplicate complaint in its name and subsequently received a reference number from the SEC acknowledging receipt. ESPN reviewed the complaint as well as an automated response from the SEC confirming its receipt of the complaint.

The attorney said he has not heard from the SEC. There is no indication an investigation has begun, and an SEC spokesperson told ESPN the regulator doesn’t comment on whistleblower complaints.

Despite not being registered with the NFLPA, Feste continues advising some of the NFL’s marquee players through KM Capital, including Tagovailoa and Mahomes, who last July signed the most lucrative contract in NFL history: a 10-year extension deal reportedly worth up to $503 million. Mahomes and Tagovailoa, who were still in high school during most of Feste’s title loan arrangement and weren’t listed in court documents in the case, are both represented by player agent Leigh Steinberg. The California-based agent also had clients who were noteholders in the title loan venture, including Brunell and Dorsey. “Joey is one of the financial planners some of our guys use,” Steinberg said. “I don’t know much about the specifics.”

Steinberg said his agency doesn’t have an investment service and isn’t involved in players selecting a financial adviser. He said financial advisers actively recruit players, and that Feste was already part of Tua’s team before his agency landed the former Alabama star.

The union official said NFLPA investigators with concerns about Feste spoke directly to players and to agents who had clients using Feste as a financial adviser in 2017, but the union did not issue a general alert about its decision to decertify Feste. Why an alert wasn’t distributed remains unclear. When first approached by ESPN, the official insisted one had been issued in May 2017 but when pressed for a copy said it had only been drafted but never sent out. The official said alerts typically target financial advisers who are not registered in the union’s program, and Feste had been.

However, a review of NFLPA alerts revealed at least three issued in recent years for financial advisers who were part of the union’s registered program. Several years prior to the Feste case, the union distributed an alert on a financial adviser, Jinesh Brahmbhatt, who, like Feste, had declined to cooperate with an NFLPA investigation. In 2016, the union issued an alert about another adviser, Jonathan Schwartz, after his business dealings were the subject of a civil lawsuit, and a third adviser, Ash Narayan, was suspended after the SEC took action against him and others over their handling of client accounts.

Securities experts interviewed by ESPN noted other red flags in the Feste case. Chase Carlson, a securities litigator who has represented dozens of professional athletes, said financial advisers shouldn’t recommend investments — in Feste’s case, the Storehouse promissory notes — in which they also have a financial interest. “To the extent an adviser is going to hand over client assets, he needs to do a damn good job of making sure that it is a sound investment,” Carlson said.

Feste is also both the president and chief compliance officer of the financial advisory firm — KM Capital Management — that had clients invested in auto title loans. Thus, as the firm’s compliance officer, he essentially polices himself, Carlson said.

The Storehouse arrangement is indicative of unconventional financial instruments often offered to wealthy clients and athletes.

“Young athletes have supreme confidence, so they don’t think it will happen to them. But when the real money comes in, athletes are fish out of water,” said David Byrne, a former financial regulator at the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA) who specializes in monitoring and auditing pro athletes’ finances. “They have no other option than to give their money to a financial adviser, many times who was recommended by their agent. And there’s no oversight by the athlete because he doesn’t know right from wrong in the financial world. It’s a total mess.”

The Storehouse promissory notes were never registered with the SEC or the Texas State Securities Board, according to spokespersons for both groups. FINRA, a government-authorized nonprofit that oversees broker dealers, cautions investors to be “wary of any pitch for a promissory note,” adding that unregistered promissory notes are not subject to regulatory review.