IT WAS NOV. 5, 2017, game nine for the newly formed superteam in Oklahoma City. After a bumpy 4-4 start, the Thunder were in Portland to take on a division rival.

Trail Blazers coach Terry Stotts had taken his spot in the narrow hallway of the Moda Center pregame to talk with reporters, and as had been the case for the first eight OKC games, a number of questions were aimed at what to make of the big three — Russell Westbrook, Paul George and Carmelo Anthony. Expected were platitudes about the talent, scoring and potential, but as Stotts plowed through the praise, he said the quiet part out loud about the Thunder.

“With all due respect to Carmelo,” Stotts said, “four of their five starters are very good defenders.”

As Stotts continued outlining his perspective on this Thunder team, his report on Anthony wasn’t meant to be a joke, or a jab, though it was sort of taken that way. He wasn’t wrong. Anthony had never been regarded highly on the defensive end. Even though he had shifted positions, playing power forward in OKC, he had still been a nightly pick-and-roll target for opposing offenses. Then, after a turbulent season in which OKC won 48 games, Stotts’ quiet hallway scouting report on Anthony hit a crescendo. It was Game 5 of the Thunder’s first-round series against the Utah Jazz. Already down three games to one, OKC trailed 71-53 and was headed for a public shaming of their so-called superteam.

Then, a run. A season-saving run. In the last seven minutes of the third quarter and the first four minutes of the fourth, the Thunder roared back, deploying wing Jerami Grant at the 4 with a hyper-aggressive, switch-everything swarming defensive scheme.

Anthony watched all of it from the bench.

After OKC was eventually eliminated in six games, it was clear to anyone paying attention: Melo wasn’t going to be back in Oklahoma City.

Then, after an infamous 10-game stretch in Houston to open the 2018-19 season, Carmelo Anthony, a man who had made 10 All-Star teams and scored nearly 26,000 points, was cut from the Rockets. His reputation was in tatters.

As Anthony’s precipitous fall played out in franchise boardrooms and front offices across the league, a different reaction emerged from his peers. There was confusion. Consternation. Outrage.

“It was a basketball crime of its purest form,” says Jamal Crawford, 21-year vet and three-time Sixth Man of the Year. “Melo is a baller. He’s a hooper. He’s a hooper’s hooper. That’s why he’s so revered and why it bothered so many people. That’s why it was so loud.”

The respect Anthony holds throughout the league never went away, even when he did. Young stars admire his craftsmanship, his attention to detail, his raw scoring power. Anthony, who is now in his second season with the Blazers and just passed Hall of Famer Elvin Hayes for 10th on the NBA’s all-time scoring list, has long been one of the most polarizing players in the game, the de facto dividing line in the debate between good shots and bad.

For players, it’s as if he’s the representation of pure hoops, the pushback against efficiency calibrations and analytics-driven decisions.

“He can’t get a job? That’s almost a slap in everybody’s face,” Crawford says. “Especially the true ballers of the league. If it can happen to Melo, it can happen to anybody.”

— Ja Morant (@JaMorant) October 17, 2020

JUST TWO YEARS removed from being an All-Star in New York, Carmelo Anthony, at 35, was jobless.

“I know myself. I believe in myself. I know what I can do. So that was the hard part at first — asking myself why,” Anthony says. “Like why? Why me? Of all people, why? Why? I was beating myself up.”

A week passed. Then two. Then a month. No one called.

“That’s just the naivety of the whole situation. It was like, ‘Somebody’s gonna call. Somebody will.’ Because it happened early in the season, it was, ‘OK somebody is gonna call,'” Anthony says. “December 15, somebody is gonna call. January, somebody is gonna call. I was kind of trying to psych myself out. And then after Christmas and New Year’s, I was just like, ‘I gotta be at peace with this, man.’ Whatever is gonna happen is gonna happen.

“I’ve got to start finding other ways to be happy. Maybe this is it for me.”

Anthony started digging into post-career opportunities in finance and technology or entertainment. He was going to his son Kiyan’s AAU games, but it wasn’t easy to show his face.

“I was embarrassed,” Anthony says. “I didn’t even want to go to my son’s tournaments. I was that embarrassed. Because it’s like, you are who you are. You’ve been in this game 16 years playing at a high level and that’s just taken away from you. Nobody remembers that. It was an ego hit. I used to tell my son and wife, ‘y’all go to this tournament, I don’t think I can handle it.’ I was broken at that point.”

For years, there was always talk of what Anthony would need to change. Change of position, change of style, change of approach, change of role.

“I had to make all types of adjustments. Mentally. Emotionally. Spiritually,” Anthony says. “The physical part I was already doing. But the mental, emotional and spiritual part was what I really had to get stronger at. And that’s what I was really focusing on and what really made me at peace with walking away from it.

“But,” Anthony says, emphasizing the counterpoint, “I’m walking away knowing that I still can go out there and play.”

For 375 days, and a full NBA season, Anthony didn’t touch an NBA floor.

Congrats Melo! One of the greatest. Simple as that. https://t.co/QIipnHKaO0

— Jayson Tatum (@jaytatum0) August 10, 2020

MIDWAY THROUGH THE second quarter of an April 13 matchup between the Blazers and the Boston Celtics, Carmelo Anthony is positioned where he’s been thousands of times: the right elbow. With his back to the basket, he gives his defender, Celtics rookie Payton Pritchard, a subtle deke, a slight tilt of the head to the right to fake as if he’s going to turn and drive over his right shoulder. Instead, he peeled back and turned over his left shoulder, squaring up against the 6-foot-1 guard.

Anthony crosses the ball right to left, then hits a mini hesitation as he drives toward the middle of the floor. Pritchard shuffles to cut it off, but after one dribble Anthony plants his right foot, turns his back to the basket and gathers the ball, spinning into a baseline pull-up. Money.

This shot, like so many of the almost 22,000 before it, is part of a sequence. It isn’t a set play or a backside screen to free him into an open pocket of space. It is engineered, built from years of laboratory work, each move interlocked to the one before it to create a picturesque 15-footer.

It’s well-documented that but for a few superstar exceptions, the midrange is an analytical crime. It is also where basketball can become an artform, where the sweat equity of individual workouts and craftsmanship produces poetry. It’s a basketball artifact.

Imagine the paradox, then, for Anthony — and for a generation of players who grew up admiring his game. That mid-range shot had made him millions, gained him international fame, had elevated him into an icon beyond the game itself. That shot is why he’s headed to the Hall of Fame on a first ballot. It’s also what he was supposed to stop doing so damn much.

“The thing that made you a Hall of Famer, you just stop, right?” Crawford says with a laugh. “How many points has Melo scored in iso? How many has he scored just sizing somebody up and going to work?”

To legendary bucket-getters like Crawford, both young and old, Anthony’s game is the distillation of hooping. It’s how you settled debates in the neighborhood, how you determine who sat on top of the food chain. One-on-one, me and you, who’s better?

“That’s why there’s a disconnect,” Crawford says. “Players look at him like, ‘We love him, because what he brings to the table, what he’s about, how we grew up.’ And now the disconnect comes because it’s, ‘OK, you guys are telling us to play a certain way, but a lot of you guys have never played at this level before.’ So it might be, I grew up watching Melo, I may have had a Melo poster on my wall, may have worn his shoe growing up. And seeing him get buckets, seeing him win.”

So many young players grew up watching him take Syracuse to a national championship as a freshman; watched him become a scoring machine in Denver and hit fadeaway jumper after fadeaway jumper in Madison Square Garden, doing it his way. Someone like Karl-Anthony Towns, 25, remembers watching Melo play as a high schooler at the Primetime Shootout in Trenton, New Jersey.

“He was always special,” Towns says. “One of the most gifted offensive players I’ve ever seen.”

Towns says he would play NBA 2K in practice mode, setting up scenarios over and over with 10 seconds left. Melo always got the ball for the last shot.

“He’s an icon, there’s no doubt about it, and if I had to put my opinion on it, he’s a first ballot Hall of Famer,” Towns says. “He’s one of the best small forwards to play this game, one of the most electrifying players this league has ever seen.”

As Crawford says, people love Anthony. Teammates, both current and former, cite his sense of humor and his attentiveness to younger players that look for advice and guidance. The way he played the game resonated with every kid picking up a ball.

As Anthony’s future in the league became more uncertain, the support he received from players never wavered. LeBron James said in Dec. 2018 he thought Melo could still play. Allen Iverson said there’s no way Melo should retire. Magic Johnson said he thought Melo still had a lot left. Zach LaVine tweeted, “Respect the hell out of Melo! Been getting his name thrown around like he’s not one of the baddest dude to put the ball in the hoop!” Taurean Prince tweeted, “Guarded him for a month straight. Same Melo only thing diff is the narrative ppl throw on his name.”

Will Barton said in Dec. 2019, “It’s crazy the disrespect a guy that good gets on social media. You look on Twitter and Instagram, they’re kind of always clowning him. But real basketball heads know how good that guy is, and he’s a special talent.” Westbrook said in Aug. 2020, “He belongs in this league. He’s shown that time in and time out.”

And on and on. Even now, when Anthony hits a big shot, a hashtag goes viral, with NBA players often contributing: #ApologizeToMelo.

Respect the hell out of Melo! Been getting his name thrown around like he’s not one of the baddest dude to put the ball in the hoop! And still is💯

— Zach LaVine (@ZachLaVine) August 2, 2019

Anthony’s legacy will endure in the influence of a younger generation of ballers, his game the living representation of every kid in their driveway. Anthony being pushed out of the game felt to many like a rejection of what basketball was about.

“I think the younger generation can kind of see their future [in Melo],” Crawford says. “Because we all grow in this game if we’re lucky enough to play 15 years. But the thing about it is, how can we let people who didn’t play at this level push out a Hall of Fame guy because he doesn’t fit their new narrative of how the game should be played. I think that’s what bothered people more than anything.”

The schism was pronounced. From his departure to his return, Anthony became a symbol, a vehicle to vent frustration about the media, or analytics or league politics.

“He should’ve never been out in the first place,” says Phoenix Suns guard Devin Booker. “And all real hoopers know that.”

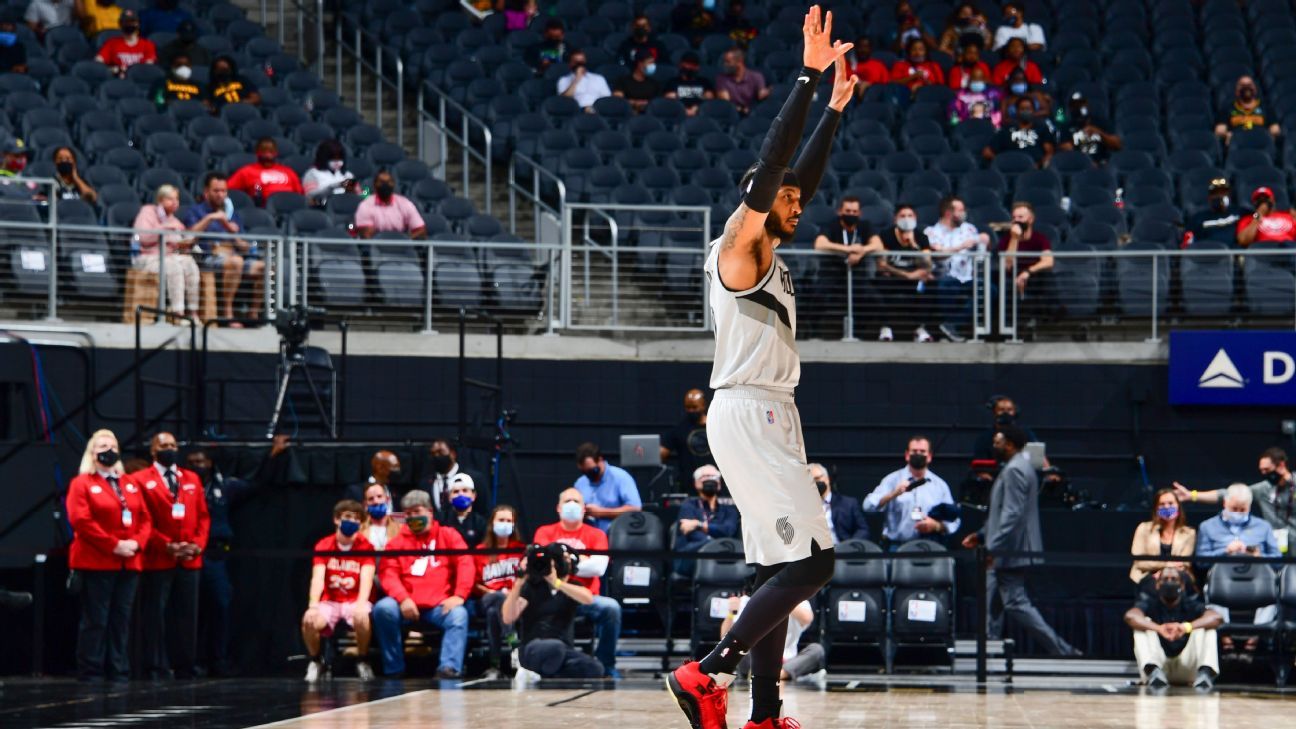

TERRY STOTTS IS standing at the front of the locker room, a ball in his left hand. It’s May 3, and the Blazers have just lost to the surging Atlanta Hawks.

“We need to acknowledge milestones, and this is a big one,” he said. “Top 10, all-time. That’s big time.”

With a handshake first, he hands the ball over to Anthony, who raises the ball into the air as the locker room erupts in cheers.

“A couple years ago I ain’t think I was gonna be in this moment. I was out the league … for whatever reason,” Anthony said to his teammates. “I’m back. I persevered. I stayed strong. I stayed true to myself and now I’m here in the top 10.”

He’d needed 10 points entering the game to pass Hayes. Forty-six seconds after checking into the game — off the bench — he splashed his first shot, a straightaway catch-and-shoot 3. Three fingers three times into the side of the head. His trademark.

“There’s not many guys that come through this league that get labeled as an icon,” Booker says. “And Melo, Stay Melo, is definitely one of those guys.”

Two minutes later, Damian Lillard drives into the paint, drawing defenders and kicking to a wide open Anthony. Same spot. Catch-and-shoot. Three fingers three times to the head.

“For me personally, he affected my life and my game from a distance,” Booker continues. “Just watching him over time. Watching the skillset, watching his passion for the game.”

Twelve seconds into the second quarter, Enes Kanter sets a downscreen for Anthony and McCollum flips the ball over to him on the wing. He’s open enough to pull from 3, but after a quick headfake and dribble, he rises into a classic Melo mid-ranger — body leaning, legs scissored — and nails it.

“He’s a hooper. A real hooper,” Booker adds. “And that will never change.”

For his ninth, 10th and 11th points, Anthony isolates on the right wing, Danilo Gallinari checking him — one light crossover through the legs, right to left to size up his defender, then one hard dribble.

With a hair of space, he pulls from 3. Gallinari overcommits and barrels into Anthony’s lower body. All net, plus the foul. Three fingers into the noggin again.

Recognizing the moment, Anthony raises both arms into the air.

Says Booker: “Melo is forever.”