If statistics around climate change are often shocking, the cause of them often isn’t.

Transportation is one of the biggest contributors to climate change, with an estimated 7 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide produced in 2020 from global mobility.

So, if managing mobility is a critical part of securing the world’s future health, is it time to stop racing cars around in circles for fun?

Or does motorsport have a role to play more than any other sport in helping to reduce carbon waste through mobility, which is considered to be between 25 and 30% of total emissions?

Traction control and lightweight parts are just a some of the technologies which have come directly to modern vehicles from research and development in motorsport – historically in Formula 1, and more recently in battery technology as more electric cars appear on the road.

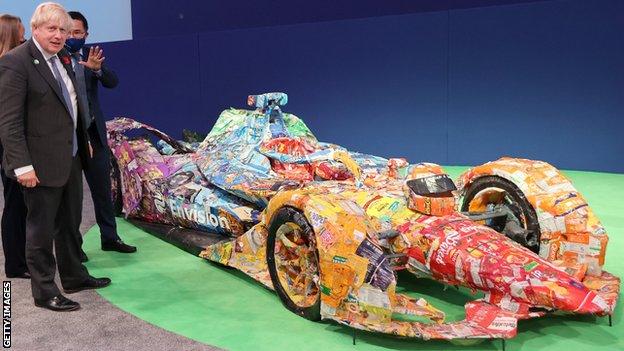

“It’s a good time to be alive if you work in this industry. We are learning more every year, and all companies are hungry for data,” says Sylvain Filippi, the amiable Frenchman in charge of Envision Virgin Racing, a team which competes in the all-electric Formula E racing series, and is the only sporting outfit at the vast COP26 United Nations climate conference in Glasgow.

“[Motorsport] is a small part of it, but one aspect is the really extreme ‘duty cycle’ [when testing a battery]. Electric racing is the hardest test of any battery, trying to draw as much power as possible, flat out, or regeneration at a very high rate. A road application is a lot smoother, so motorsport is a giant testbed for this technology.”

Formula E uses battery technology in its cars and has helped to accelerate progression in electric road cars since its inception in 2014, when drivers had to stop halfway through a race to jump into an identical car after the battery ran flat.

The motorsport world raised an eyebrow at first, but now Formula E’s ‘Gen 2’ cars easily manage a race distance with performance to spare.

Filippi and his team have arrived at COP26 with a battery that goes further.

Partnering with Johnson Matthey, they have made a two-seater racing car which can drive guests around at breakneck speeds thanks to technology which has about 20% greater energy density than electric vehicle technology on the road today, which equates to faster recharging and allows cars to travel further.

Part of the challenge of battery technology is to extract as much energy and power from a certain size of battery cell as possible – in the case of most road cars, lithium-ion.

“What’s really exciting with the two-seater racecar technology is we can show that it exists. We can test it in an extreme way on the racetrack. Once you get to high levels of energy density then it conjures up a lot of possibilities.”

It doesn’t stop there, either. Filippi believes the advancement made by his team benefits a future for more than just those who can afford a Tesla.

“We are close to reaching the threshold of heavy-duty vehicles, such as long-haul trucks and vans – which people said they’ll only be hydrogen powered – where you can now store enough energy in these batteries, to make the business case to say: ‘OK, I can carry a lot of stuff and my truck can do several hundred miles.’

“There is no holy grail as such. The people more clever then me – the chemists – will figure out separate sources for each application. Innovation every year means that we still make this arbitration between energy and power, but the overall threshold is increasing every year, so for the same power as last year you can have more energy, or vice versa.”

With the advent of an electric motorbike series MotoE and, in 2021, the first year of Extreme E SUV – the off-road sister to Formula E – the battery revolution is already diversifying.

So even if the much-maligned 4x4s outside the school gates are here to stay, the gas-guzzling label may soon disappear. Especially given high-profile names such as seven-time Formula 1 world champion Lewis Hamilton are putting their names to teams – as he has in Extreme E’s case.

Another road to take

Speaking of F1, motorsport’s most high-profile series has been highlighted as the dinosaur in the room when it comes to relevancy in an age when fossil fuels simply cannot continue to be used at the current rate.

“We can’t have a sport which is seen as out of step. We will always be mindful of that,” said F1’s managing director for motorsports and multiple title-winning team boss Ross Brawn in July.

“We have a one-and-a-half-hour race, we have 1,000-horsepower cars, we are the pinnacle of motorsport. You can’t get that bang without fossil fuels,” he adds.

But the sport acknowledges that if fuel remains integral to mobility, fossil fuel will have to be replaced by a synthetically produced fuel that is sustainable.

Synthetic fuels use carbon captured from the air, farm waste or biomass. But critics say the carbon produced in making synthetic fuels could offset the benefit.

“We believe that multiple technologies will be required to sufficiently reduce greenhouse gas emissions from the transport sector in line with the Paris Agreement targets,” reads a statement which makes up part of F1’s climate action strategy.

“In 2025 our aim is to unveil the new Formula 1 engine, and it will be a 100% sustainably fuelled [second generation] hybrid engine that will be carbon neutral but maintain the power and speed we expect,” it adds.

“We aim to make this a drop-in fuel [to avoid expensive engine conversions] and are in advanced discussions with fuel companies to create the volumes needed for the sport but also scaling up for wider social use.”

Following an audit which showed that F1 produces about 250,000 tonnes of carbon waste each year, the sport has pledged to have a net zero carbon footprint by 2030 – something Formula E achieved last year, albeit with about 15 fewer races to consider the logistics for.

F1 also points out that of the 1.4 billion cars on the road globally by 2030, only 8% will be pure battery electric, leaving more than 1.2 billion vehicles which have internal combustion engines, including hybrid cars.

“Electric vehicles are more expensive, pricing out certain sections of society and that such technology has its own environmental impacts, such as making and disposing of lithium batteries, and that charging the batteries can come from grid electricity generated by fossil fuels,” it adds.

A marathon, not a sprint

It seems a lot of the mind-boggling costs and challenges of infrastructure to serve either battery power or sustainable fuels are still unknown.

But it is not just F1 of the older motorsport platforms who are adapting. The World Rally Championship is using hybrid technology from 2022, and sportscars are generating interest from their own revised hypercar rules. They have seen a number of car manufacturers rejoining the World Endurance Championship (WEC) from 2023 – which includes races such as the Le Mans 24 Hours.

Ferrari, in particular, have been attracted back as a top-level competitor to the series for the first time since the mid-seventies, when Steve McQueen presided over a golden era which saw cigarettes and oil, rather than cleaner air and water, as badges of honour.

Some other teams have decided to return after leaving Formula E, such as Porsche and Audi. Along with Peugeot and Cadillac they have been attracted by a hybrid technology that gives manufacturers a much broader set of rules by which to innovate, instead of other series’ more constricted parameters.

There is even a hydrogen-power class planned for 2025.

“Endurance racing is the ultimate test for all road-related products,” says Fredeic Lequien, WEC CEO.

“When it comes to sustainable development, we – alongside the ACO Le Mans [organisers] – will continue to help deliver our part in sustainable mobility.”

From next year, French oil firm TotalEnergies has created a 100% sustainable bioethanol fuel from wine residues in France, as well as feedstock. They say the fuel will see a reduction of CO₂ emissions by 65% in the cars.

“Endurance racing, by its nature, has always served as an excellent research and development platform and it is an important milestone to have the FIA World Endurance Championship switching to 100% sustainable fuel,” says Jean Todt, president of motorsport’s governing body the FIA.

“It’s FIA’s major goal to implement sustainable energy sources across its portfolio of motorsport disciplines, thus paving the way in the reduction of CO₂ emissions, perfectly reflecting our race-to-road strategy.”

Back in the COP26 blue delegates’ zone, Filippi is a convincing advocate of batteries as a solution, but acknowledges a blend of technologies could be applied to aid the reduction of greenhouse gases.

“It’s exciting. In next few years we can get to a point where we don’t even need to choose between [energy and power density], then just the size of a power pack for a long-haul truck needs a 500-or-more-kilo power pack. Or a 70-kilo pack for a road car doesn’t need much more energy, so the weight of the same car can be 200 kilos lighter than now.

“Aviation is the most challenging of all, because every kilo carried can make it pretty tricky, but at least we can get things going. And every year we improve by 10% – give it another five years and anything is possible.

“It’s proven if you put all motorsport engineers and simulations and resources into a problem you tend to accelerate slightly the rate of progress – that’s usually what tends to happen.”

The need for speed, it seems, has never been more important.