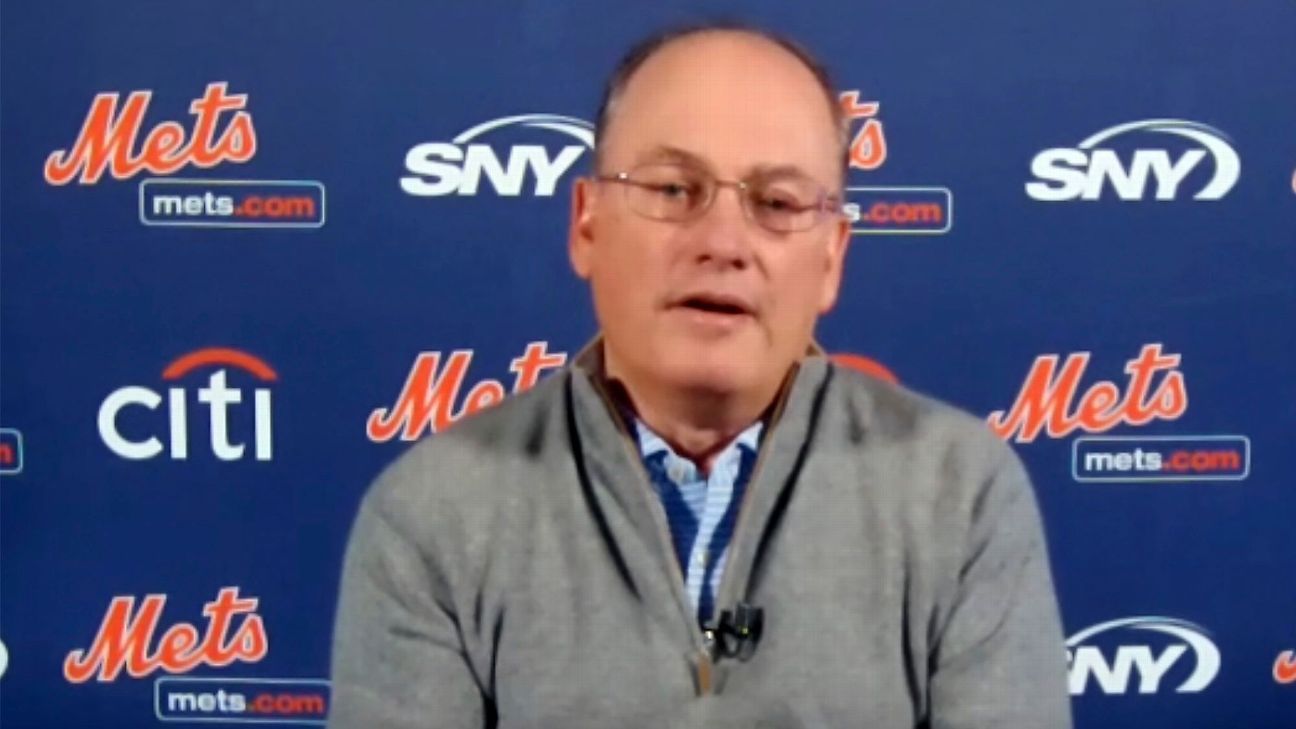

It must’ve felt good for Mets owner Steve Cohen to punch send on his angry tweet Wednesday morning, his vitriol and endorphins and frustration released by directing his social media ire (and his more-than-200,000 followers) toward little-known agent Rob Martin. Cohen referred to Martin’s actions in the Steven Matz negotiations as “unprofessional” and all but called him a liar.

I’m not happy this morning . I’ve never seen such unprofessional behavior exhibited by a player’s agent.I guess words and promises don’t matter.

— Steven Cohen (@StevenACohen2) November 24, 2021

What Cohen doesn’t seem to understand, or care to acknowledge, is that every time he publicly gripes about agents, his offense, or the fans, he is denting the franchise that cost him $2.475 billion. Tweet by tweet, he is feeding the perception among rival executives and agents, and, most importantly, among players, that the Mets have somehow become more dysfunctional under Cohen than they were under the Wilpon family, the previous ownership group — and that is an extraordinarily high bar. He is feeding the perception that the Mets are evolving into their own Big Apple Circus, with the owner looming as a threat to attack everything from agents to slumping hitters.

It’s hard to understand how professional hitters can be this unproductive.The best teams have a more disciplined approach.The slugging and OPS numbers don’t lie.

— Steven Cohen (@StevenACohen2) August 18, 2021

With each social media post, Cohen probably makes it a little more difficult for the franchise to realize his stated goal of winning the World Series in the next two to four years. In a sport in which players must be courted, and building organizational success and an enduring major league roster can take years, perception does matter. When you talk with rival officials — including some who’ve had opportunities to talk to the Mets about employment — the simple truth is that Cohen’s ownership habits are viewed as an unwanted wild card.

And in 2021, front-office types and players seek as much information as possible because they want as much certainty as possible. One executive said during the summer that if the Mets reached out to ask him or her about a job near the top of their organization, reporting to Cohen, the answer would be concise: “No. No. No. No. No. No. No. No. No. No. Never.” (That is, to be clear: 10 “no” answers, and one “never.”)

Cohen took over the Mets little more than a year ago, and he can still land players and front-office executives because of the money and the opportunity he can dangle. Billy Eppler, fired by the Angels after the 2020 season, jumped aboard. But even then, as a respected agent who had nothing to do with the Matz negotiations said last week, “Thank god for Billy that he got a four-year deal.”

It’s possible that Cohen and Eppler will bet on the right players, that the sport’s richest owner could forge a path no one envisions, all while he narrates the ups and downs of that journey to fans on his Twitter timeline.

But it’s also very possible that he’s repeating the same mistakes that many, many first-time owners have made in assuming that he can apply a skill set from an industry outside of baseball and force his competitive will upon a sport that no one can control.

Most of his tweets are funny and harmless, and, as he indicated in a recent interview on WFAN, they are a way for him to link directly with his paying customers. Some of his activity on social media, however, can backfire — which is exactly what happened Wednesday, according to the chuckling by several longtime agents and baseball executives over Cohen’s minirant against Martin. They spitballed some of the mistakes they see in what he is doing:

1. They think Cohen looks like, at best, naive; at worst, out of touch when he complains about how an agent done him wrong. “Welcome to the club,” laughed one high-ranking executive, who says a good working guideline is to assume that no deal is actually completed in writing. “Every general manager has a story like that. Not everybody does business the way you’d like them to.”

It’s like an outfielder complaining about the sun getting in his eyes, a pitcher whining about his catcher’s signs. Get over it, and move on. It helps nothing to complain out loud, and it often hurts. The more Cohen exhorts out loud, the more he is viewed as unpredictable — and a headache that many players and executives decide isn’t worth the trouble.

George Steinbrenner provided examples of this in his years as the Yankees’ owner. Initially, his ambition and money lured the likes of Catfish Hunter, Reggie Jackson, Goose Gossage and Dave Winfield. But by the mid-80s, as Steinbrenner seemed to hire or fire Billy Martin every other year in what was called the Bronx Zoo, the Yankees’ primary role in the free-agent market was as a tool of leverage for agents and players who would use Steinbrenner’s offers to get more money from more attractive situations. It wasn’t until after Steinbrenner was suspended and largely muted his organizational invocations that the 1996-2001 dynasty was built, and the Yankees became a free-agent destination.

2. Cohen’s tweet Wednesday will be used against the Mets in upcoming negotiations. “Every agent sees that [anger] and will look at it as desperation,” said one executive. “They see a team that needs [starting] pitching and an owner who’s pissed off, and so now they can feel confident walking in [to a negotiation] setting a higher bar.”

At the moment, the Mets’ rotation is a mess. They don’t know what they’re going to get out of Jacob deGrom or Carlos Carrasco because of those pitchers’ respective injury histories. Noah Syndergaard has already left the organization, to sign with the Angels, and Marcus Stroman is a free agent and listening to other teams.

They need help, and following the Mets’ miss on Matz — and Cohen’s complaining — agents for other unsigned players are bound to call Eppler generously offering solutions — in return for a lot (more) of Mr. Cohen’s money.

3. It’s not hard to see that Cohen is deploying particular reporters to get his message out, a rookie mistake that will inevitably boomerang on him in a city like New York. “You can see it from a mile away,” said an executive who is a veteran of a big market. “You’re just asking for trouble.”

Joe Torre, the former Yankees manager, was a working model in how to handle a city full of competing reporters and columnists: he generally kept everyone at arm’s length and provided the same access across the board. Torre rarely — if ever — talked to one reporter on the record while declining to speak to others. Even Jeff Wilpon, the Mets’ previous owner, was more deft in his handling of reporters, positioning himself to be the source of information — which appeared to inoculate him from some of the criticism that he deserved.

Cohen’s early tactics are setting him up for an avalanche of backlash if the Mets don’t win — and the more aggressive he is in his public posturing, the more difficult his challenge might be. Last week, an American League official noted that in baseball, you can’t buy a championship, and you also can’t buy clubhouse culture. All of that has to be fostered, carefully. If Cohen wants to connect with fans, he needs to wade into the fray at winter events and during games at Citi Field, sign autographs, pose for pictures. And most importantly: build a winner, slow and steady.

But if you polled the Mets’ rivals, they would love for Cohen to keep going rogue, to keep pushing send and tweeting impulsively — and standing out among his peers for all the wrong reasons.