It is a quiet scene, not germane to the plot or destiny of any of the characters, but it is one of the most powerful in the new film “King Richard,” Will Smith’s biopic of Richard Williams. Richard and his wife, Oracene Price, (played by Aunjanue Ellis) watch on a small television the news footage of March 3, 1991. Motorist Rodney King is being beaten by members of the Los Angeles Police Department while surrounding police officers watch. Oracene offhandedly comments something to the effect of, “At least they have it on video this time.” In the next room, Richard and Oracene’s girls, tennis prodigies Venus, then 10, and Serena, then 9, with their sisters, Yetunde, Isha and Lyndrea, are shrieking and playing and carrying on as kids do. For the film, it is just another news item of daily injustice — but one containing the hope that the existence of video will finally justify a reality much of the country does not believe exists.

For the remainder of the film, there is no further mention of the King beating, nor does the movie acknowledge its bloody denouement the following year — a five-day uprising that left more than 50 people dead, more than 2,300 injured and an estimated $1 billion in property damage to South Central L.A. after a predominately white Simi Valley jury acquitted the four officers. “King Richard” is about a man with an outlandish, quintessentially American idea of entrepreneurship — that his two youngest daughters are tennis geniuses (“I have a plan,” is the film’s foreshadowing mantra), and for two hours, 24 minutes, the film follows his relentless and unshakable faith in that plan, no matter how many upper-crust blue bloods or nosy neighbors treat him as a crazy man.

Yet, in that brief moment on the television, when LAPD officers are mercilessly beating King, the state metaphorically is beating Black America — and a movie ostensibly about a legendary tennis story set nearly 30 years ago is soberingly contemporary. The King video did not translate into justice this time. What followed was not a repudiation of police violence, but an escalation of it, which stood as a haunting counter to the film’s universal themes of hope and determination. The specter of injustice against Black people is a living, breathing component of “King Richard” — and in no small way, the movie owes its very existence to it.

This upcoming Feb. 26, a decade will have passed since George Zimmerman, the self-styled neighborhood watchman turned vigilante, killed 17-year-old Trayvon Martin in Sanford, Florida. Zimmerman believed Martin — young, Black and wearing a hooded sweatshirt — to be a threat. Zimmerman called 911, was told by a dispatcher not to engage with Martin, ignored the command and proceeded to shoot and kill the teenager anyway. Three weeks later, Miami Heat players, led by Dwyane Wade and LeBron James, posed for a team photo wearing hoodies as a tribute to Martin and a message of support to his family. That moment represented the end of a chapter in American sports.

Zimmerman’s killing of Martin in 2012 changed America — its dialogue, its actors and most starkly, its pretenses. And it was only the start, just one bookend in a saga. The murder of George Floyd nearly eight and a half years later would become the other. In the tumultuous years in between, sports and the country have been ripped asunder, transformed, dehypnotized. Black athletes were released from the 40-year stupor of sociopolitical disconnection, the nation from the sumptuous fantasy that an Obama presidency would at last carry the country into its elusive post-racial Eden. The reality has been anything but.

Throughout Obama’s two terms lurked fear that his presence would produce some form of physical recompense for centuries of Black suffering. His reassurances that he was a president who just happened to be Black were framed through a plea for unity. He reminded Americans of, in his words, “our common creed,” rarely distinguishing a peril specific to Black people — until Martin’s killing, when he did. Trayvon Martin could have been his own son, he said. It was an innocuous, human response that was met with such a revealing hostility, for Zimmerman did not belong to law enforcement. He represented no formal institution with which other white people could identify — except the institution of whiteness. He was just a guy. But the harsh reaction to Obama was demarcating, ostensible proof to his enemies that he did favor Black people after all — and a reminder that politicians, like creatives and academics, often are dissuaded and prevented from advocating specifically for Black people. Eight years after Obama, Kamala Harris during the 2020 campaign reassured voters in an interview that she wouldn’t make laws benefiting only Black people. It is a playbook.

The backlash was defining, and the combination with the Heat photo — the world’s most powerful Black man and its most recognizable Black athletes publicly denouncing the killing of a Black boy — created a flashpoint. For the first time in nearly a half-century, the dormant, super-rich Black athlete would speak — and be called un-American for it. Sports would become the staging ground for the dueling collision of patriotism and protest. America, shorn of the myth of post-racialism, was free to act out — and the country has been tearing itself apart ever since.

The Ferguson uprising in 2014. Freddie Gray’s death while in police custody in 2015. Zimmerman’s acquittal and the equally revealing celebration of it. The arrival of the term Black Lives Matter and the hatred toward it. Colin Kaepernick’s protest in 2016. Racial violence in Charlottesville in 2017. Breonna Taylor and Ahmaud Arbery in a pandemic-ravaged, unraveling 2020 highlighted most horrifically when Minneapolis Police officer Derek Chauvin knelt on Floyd’s neck for nearly 10 minutes until he died. Even the corporate class could not continue selling beer, cars, cool and capitalism as hope without acknowledging Minneapolis and its subsequent nationwide protests. Some type of response was inevitable. The country had collectively witnessed a public murder.

At least they have it on video this time.

What I saw

Film cannot be separated from its times. When Ronald Reagan was elected president in 1980, part of his mandate was to restore pride in a country sagging from inflation, a 444-day hostage siege in Iran, the ever-growing fear of a “missile gap,” the unacceptable belief that the Soviet Union could destroy the world more times than could the United States — but most importantly, the lasting, unresolved wound of the Vietnam War. On screen, the 1980s attempted to avenge America’s defeat, give it dignity, from the cartoonish Rambo “First Blood” (1982) and its many sequels, to “Platoon” (1986), “Full Metal Jacket” (1987), “Good Morning, Vietnam” (1987), “Hamburger Hill” (1987), and “Born on the Fourth of July” (1989).

“King Richard” did not feel like an escape from the real-life, decadelong conflict occurring outside of the theater, but an extension of it. Before people took to the streets and blocked airports, before ballplayers took to their knees, and before the trauma of police violence against Black people became as common a sight on social media as cat videos, it is unlikely the Rodney King scene would appear in this type of film. Even a cursory nod to an infamous national event might have required a certain amount of courage on the part of the filmmakers to insert into a tennis movie. Nor, without the upheaval of the past decade would there have been an urgency for Smith to counter the historically negative images of Black men on screen with this film, as there now is for Hollywood to greenlight a film rooted in the generally unremarkable act of a man devoted to his children, even children as gifted as Venus and Serena Williams.

Within this time and moment, however, this subtle insertion into the film’s simple premise felt appropriate, even vital, for it identifies the long-standing presence and reputation of police in Black communities from a Black perspective, serving as a harbinger while Smith attempts to provide Richard Williams the dignity of his quest. He is not safe from predators in the community — or from the state.

Venus and Serena Williams served as executive producers on the film. The script, written by Zach Baylin, is direct and uncomplicated, rooted in the solid, constant presence of a Black father figure, anchored by Smith’s monologues of self-reliance, hard work and the memories of a life (never shown on-screen save for the kids witnessing Richard being bloodied in real-time by a local gang member outside the tennis courts) of determination against humiliation. The truth, of course, is another story altogether, and while Richard Williams was stern in his commitment and unshaking in his love, his flaws were not always the virtues Hollywood massaged them into, easily forgiven as tough love without consequence to himself or family. Like the scene where Richard attempts to teach the girls to be humble in victory by leaving them at the corner store, nearly making them walk 3 miles home. Only Oracene’s intervention prevented a cruel abuse.

Richard buys his children ice cream. He dotes on them. He is hard on them. They kiss him on the cheek. He provides them the no-excuses, no-handouts American pathway. (“If you fail to plan, you plan to fail,” a sign he famously hangs on the back fence of the public tennis court before every practice session.) He takes physical beatings from the world for them, determined his experience will not be theirs. Oracene, the nurse, expertly patches him when he bleeds. The Black man is an important part of the family.

Smith’s Richard is a two-hour corrective to the infamous Sports Illustrated cover of May 4, 1998, the lead story centered on the Black male promiscuity and abandonment of paternal responsibility of NBA players that was accompanied by the headline, “Where’s Daddy?” He is a devoted father, a complex father, a present father, and “King Richard” is primarily a simplified family story, which, in comparison to the toxicity that historically surrounds Black men on screen, is meant to feel revelatory.

The after-school special

As rubber bullets cut through the air in Minneapolis during the protests following Floyd’s killing, aimed at middle-class white people, the bill on the effects of post-Trayvon Martin America had come due. The country was coming apart. Much of the corporate class, forced at last to see its true self, looked in the mirror and saw scores of industries that had never sufficiently promoted Black employees. While covering the shortcomings of other industries, none is more guilty of whitewashing than traditional media — print, radio, television, film — and it must be remembered that during the tumult, the dissenting voices (#OscarsSoWhite, for example) have grown louder. After Floyd’s murder came an unprecedented opportunity for Black people to have a greater say in what stories get told, how they are told and who is allowed to tell them. Phones rang that had been silent for decades. Dozens of companies — especially in publishing and Hollywood — hired more African Americans into leadership roles in one year than over their previous 50. The number of firsts for Black people heading departments or joining the executive ranks for the first time during the second decade of the 21st century was an embarrassment spun as triumph, as Black excellence. But it should never be forgotten that the corporate world did not reach a collective realization in 2020 that Black people were talented enough to lead — or their work was suddenly good enough to be considered for the top awards in the nation — until George Floyd was murdered. Career opportunities, at long last, came after the protests and the funerals. It wasn’t the merit that finally moved the corporate class. It was the murders.

Emboldened with the power to shape, to be in halls of greenlighting power few Black people had entered, came a mandate. Both white executives, who did not want to offend the spending customer, and several newly minted Black executives, who were tired of Black life being depicted only through trauma and struggle, brought a new call for how African Americans should be seen on screen: uplift. This coincided seamlessly with white executives’ desire to avoid offending white audiences who came to film to be entertained, not admonished for their racism.

The result is a string of projects that, searching for the right balance, find themselves aimed at younger audiences where the storytelling can find inspiration, the majority white audiences can feel hope and diminished guilt, and the American Dream can remain intact. Over the past decade, it has proved itself to be financially successful and reliable formula, but at the cost of mature, defter storytelling. By attempting uplift without the trauma of life, the films take on a by-the-numbers, inoffensive tone of an after-school special. These movies are being asked to do too much.

Within this post-Trayvon Martin decade, several projects have fallen into a similar, entertaining but unsatisfying space, from “42” (2013) to “Selma” (2014), “Hidden Figures” (2016) and Colin Kaepernick’s Netflix series “Colin in Black & White” (2021). Each mimics a pattern of easily discredited racism while insisting the pathway to American success remains as viable as ever for those willing to apply themselves. Aspiration is always respected, even from adversaries, the difficult edges of white hostility lathed smooth — a prerequisite unfound when considering the sensibilities of Black audiences, which have had to endure gratuitous violence against their people — Quentin Tarantino’s infamous “dead n—– storage” dialogue and rape of Ving Rhames’ Marsellus Wallace character in “Pulp Fiction” (1994), for example, or the predictable racial slurs in a Scorsese film — as the price of the ticket.

Unknown, of course, is how much the original script and Black creative vision of these projects survived the hostile space of an industry essentially forced by societal upheaval to change who is in the room — while keeping the storytelling formulas intact.

“King Richard,” unfortunately falls into this fatal category, though the hostile country club scenes are painfully and (darkly comically) authentic along race and class lines where even the vindicated Richard cannot cleanly take a victory lap on some of his earlier nonbelievers because ultimately, they are white and rich and he is not. Maybe he did tell them so about his girls, but for them, life went on as rich and white. There will always be another business deal.

Black cinema attempting to land too often in the aspirational space may be lucrative, but with neutered storytelling can also be seen as counterprotest cleverly spun as Black excellence. Uncomplicated and uplifting approaches to complicated and complex narratives send the message that ultimately, there is no need for being in the street, no need to protest, no reason to reform, defund, reimagine. Rather, they suggest the existence of a pathway that barely exists, available only to the geniuses whose talents are so enormous that no businessman could say no to — such as Venus and Serena, two one-in-a-millions.

It is asking fidelity to a pathway that today, in 2021, is under vicious assault. The Washington Post has written extensively about this country’s attack on voting rights targeted at Black and brown communities. The national discourse in education is currently centered on states prohibiting the teaching of Black history. The University of Texas recently halted a study that teaches white students about anti-Black racism.

Yet, in the midst of this real-life diminishment amid increased hostility, telling important stories geared toward ninth-graders sells the fiction that the American dream is more available for Black people than ever, even that post-racialism is alive. It is not.

Make it plain

The success of any film begins with the audience agreeing to follow its director on the journey. At any point, disbelief in that journey portends certain doom. Approaching the Williams sisters as an inspirational coming-of-age story was the safe and navigable choice, falling into the family-friendly age demographic, consistent with this current strain of the Black cinematic biopic in post-Trayvon/Floyd America. But there is nothing safe about the Williams sisters or their legendary father. The choice to end the film at Venus’ 1994 professional debut in Oakland was a curious one. Serena had not yet turned pro. (She would a year later.)

The film chose to lean into Venus’ rise before Serena’s onrush. This is the safe ground. The film could safely ridicule the racists and the nonbelievers — the early tennis coaches, the snickering, faceless country clubbers, no one of real-life consequence — without upsetting the members of the game’s professional establishment (and there were plenty) who were equally racist and nonbelieving of Venus and Serena — or simply didn’t want them there no matter how good they were. The film chose to lean into Richard’s self-belief in his aspirational plan for his daughters without the payoff of giving audiences what they ostensibly paid for: the sunburst of the greatest pair of siblings to ever play professional sports.

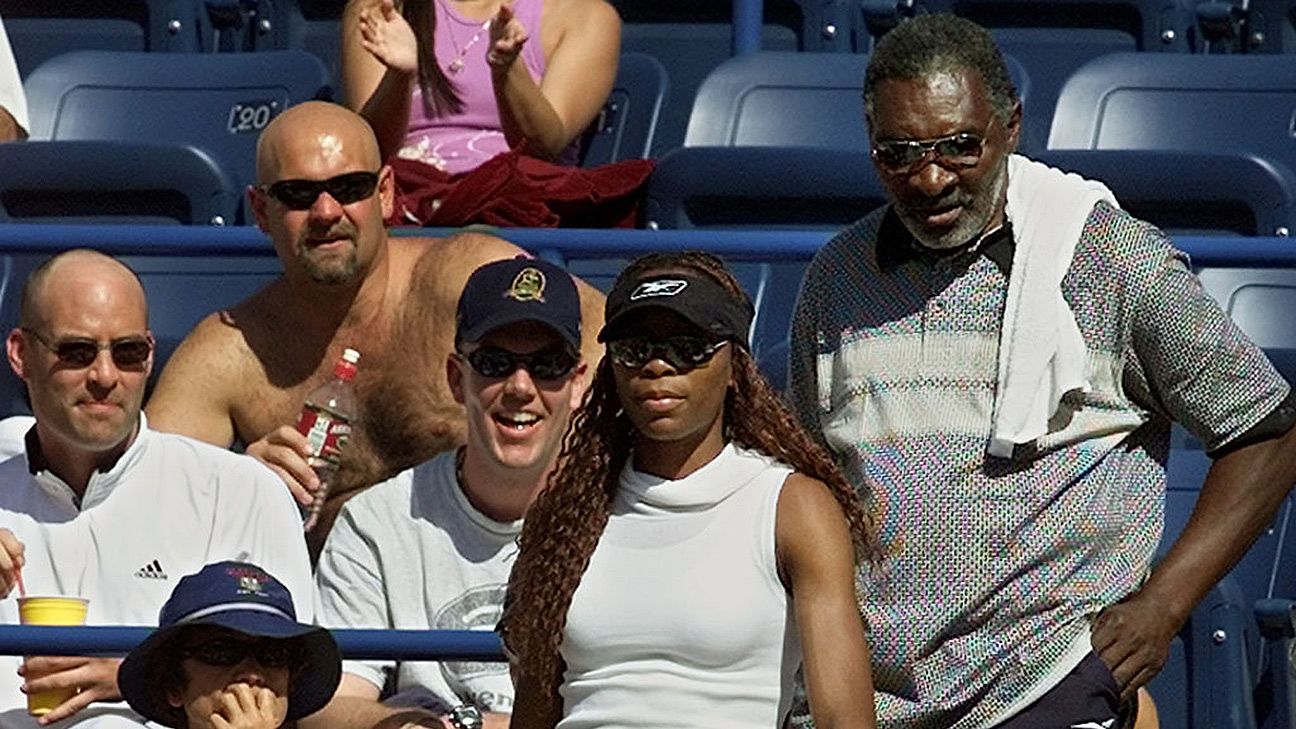

Focusing on the sisters before Serena even turns pro diminished the possibility of criticizing the current tennis establishment — like Williams sisters nemesis Martina Hingis, the great Swiss Miss who often complained about them, most loudly when their hair beads might fall loose on the court — or its current broadcasters, being embarrassed by how Richard and his family were often treated in their world-class venues. The movie ends before the most infamous incident, Indian Wells 2001, when Venus and Serena were verbally pelted with racial epithets after Venus withdrew moments before a Venus-Serena semifinal. Neither Venus nor Serena would play Indian Wells for another decade and a half.

“Remember,” Richard told me when we spoke at Wimbledon a decade ago, “they never wanted any of us here.”

For those lucky enough to have lived through peak Venus and Serena, “King Richard” missed a tremendous opportunity to recreate a time of true Black excellence, when Richard Williams and his two daughters were the most feared trio in tennis. Venus was No. 1 in the world and Serena then became No. 1. They traded majors, with an inevitable, uncomfortable tenseness when the sisters had to play each other and the parents remained impossibly neutral — and Richard’s real-time victory lap (the plan worked!) was seen as boorish, beneath country club tennis manners. He may have been right, but to them his behavior was the equivalent of not knowing his bread plate is on the left. In response to his vindication was their rage, and it was common for the tennis establishment to accuse Richard of “fixing” Venus-Serena matches, WWE-style — as the Russian Elena Dementieva suggested in 2001. Their excellence was marred by the pernicious accusation Richard was determining ahead of time who would win their confrontations.

Sports films generally suffer from a fatal flaw: Actors are rarely good athletes. Corbin Bernsen, Wesley Snipes and Charlie Sheen in “Major League” (1989) defy even the most liberal application of suspension of disbelief. Tennis is particularly difficult to recreate, as Shia LaBeouf in “Borg vs McEnroe” (2017) or Kirsten Dunst showed in “Wimbledon” (2004). In “King Richard,” the on-screen tennis is excellent by both Saniyya Sidney (Venus) and Demi Singleton (Serena).

Balancing the tension of sister versus sister was when, in the same tournaments, they would combine forces in doubles and destroy the competition there, too. The rest of the field knew. First there was one, then the other, and now both on the same court.

Certainly, the marketers and the moviemakers saw Venus and Serena through the inspirational prism of racial triumph, and theirs is a Lotto-winning success story. Unlike Tiger Woods, Venus and Serena have a legacy in the form of a generation of Black and brown girls who became pros. A contemporary on-screen Serena would have unleashed her significance to the current moment, and explained why women — Black women, especially — see themselves, every day their humiliations and struggles through her, and in turn are so protective of her. Certainly, the film leans into their first steps on the journey — and it is a fine film within that limited scope. Maybe Serena is planning some form of sequel, since her professional tale remains to be told.

Perhaps it was the editorial choice to leave the real story, the 30,000-foot story of Venus, Serena and Richard, on the laptop that was the most disappointing. The Williams sisters’ story is far greater than the cookie-cutter after-school special that might just win Will Smith an Oscar. The film avoids explaining how Richard’s plan was based on racism itself: He saw the generally waifish, less athletic and less rigorous physical standards of women’s tennis as the sport’s fatal consequence of whiteness, class and privilege — of not having to compete. Through that lens, Richard saw opportunity of applying the Black athletic standard of track and basketball to tennis. In the white world of tennis, Richard saw a vulnerability, an opportunity. His girls, if they learned the fundamentals, would have a superior advantage they would not have if they were competing against other Black athletes in the 100-meter dash.

Recognizing that vulnerability remade tennis. Their sheer power determined who would have a future in the game — and who would not. The first prerequisite, for the Black girls who wanted to be like them — for the white American, European and Australians who did, too — was to be able to hit like them. Women’s tennis now required better athletes. Once, women could serve and volley, drop shot and lob and win championships. Once the sisters arrived, tennis coaches wanted to know one thing about virtually every new prospect: if they had enough raw power to counter the force of Venus and Serena. If not, coaches would find one who could.

One day, Richard and I sat at Wimbledon and he talked about his love of Hingis. “She was a wizard, a true tennis player,” he told me. He went on at length, marveling at Hingis’ hands and touch, feel and guile — all of the magical finesse. He did it with admiration and a wistful smile, out of respect for her game, and perhaps for his true victory: the recognition that his plan, through his daughters’ talent, had turned Hingis — and the century-old history of the women’s game itself — into an anachronism.