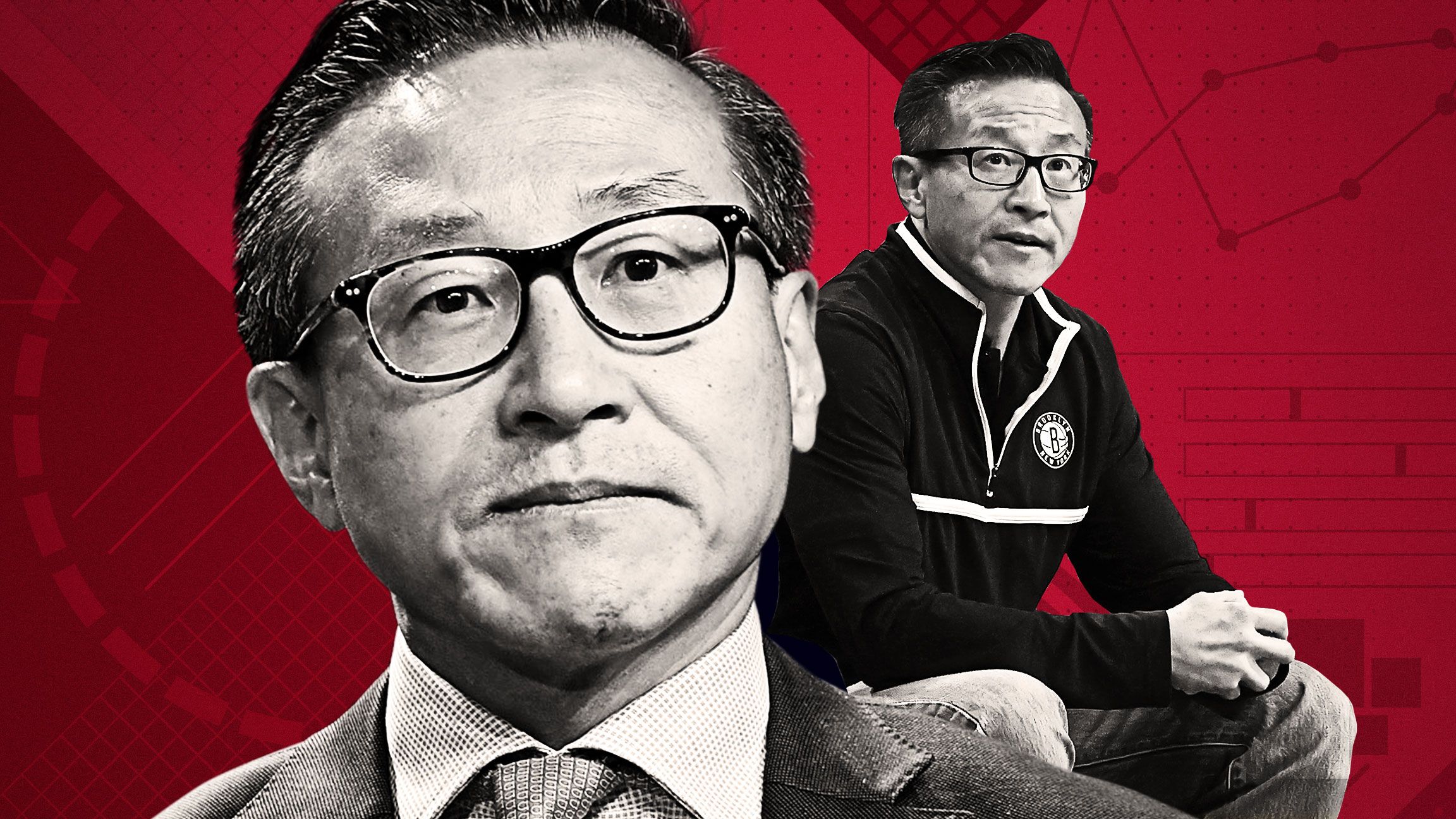

JOE TSAI, THE billionaire owner of the Brooklyn Nets, made his fortune in China. His company, Alibaba, began in a Hangzhou apartment and has since been described as “Amazon on steroids.” When Tsai bought into the NBA, commissioner Adam Silver predicted he’d be “invaluable” to the league’s expansion in the world’s largest market.

Two and a half years later, Tsai personifies the compromises embedded in the NBA-China relationship, which brings in billions of dollars but requires the league to do business with an authoritarian government and look past the kind of social justice issues it is fighting at home.

In the United States, Tsai donates hundreds of millions of dollars to combat racism and discrimination. In China, Alibaba, under Tsai’s leadership, partners with companies blacklisted by the U.S. government for supporting a “campaign of repression, mass arbitrary detention and high-tech surveillance” through state-of-the-art racial profiling.

Tsai has publicly defended some of China’s most controversial policies. He described the government’s brutal crackdown on dissent as necessary to promote economic growth; defended a law used to imprison scores of pro-democracy activists in Hong Kong as necessary to squelch separatism; and, when questioned about human rights, asserted that most of China’s 1.4 billion citizens are “happy about where they are.”

A former college lacrosse player with investments in the WNBA, Major League Soccer and professional lacrosse, Tsai sees himself as a bridge between two increasingly polarized cultures, according to sources close to him who spoke on condition of anonymity. He believes China’s restrictions on personal freedoms have paved the way for economic development that has improved the lives of millions of its citizens.

But his positions and association with companies implicated in human rights abuses have drawn criticism from a bipartisan collection of U.S. officials, human rights activists and academics focused on China.

“Joe Tsai is emblematic of U.S. sports and business figures who are critical of American imperfections, as we all should be, but who make excuses for human rights atrocities committed in China, where he makes money,” said Matt Pottinger, a former deputy national security adviser and China specialist in the Trump administration. “We’re going to self-censor or even compliment the policies of a totalitarian dictatorship that’s committing crimes against humanity?”

Tsai declined to be interviewed for this story.

An ESPN examination of Tsai’s record — and the China investments of all 30 NBA teams’ principal owners — shows how the league’s global ambitions come in conflict with its commitment to social justice. In 2019, a pro-democracy tweet by then-Rockets general manager Daryl Morey exposed the political land mines faced by the league as it navigates the tension between value and values.

The NBA still hasn’t recovered from Morey’s now-infamous tweet — an image that read: “Fight for Freedom. Stand with Hong Kong.” Banned from state TV for most of three seasons and shunned by some sponsors, the league operates under sanctions that have cost hundreds of millions of dollars and “years of goodwill,” an American coach who spent years in China told ESPN.

Within two months of taking control of the Nets, Tsai inserted himself into the controversy. Morey’s supporters believed Tsai was pushing the NBA to fire Morey and offer a full-throated apology, part of a behind-the-scenes drama that reached the White House and has not been previously disclosed. Tsai also published an open letter that accused Morey, inaccurately, of “supporting a separatist movement.”

Both the Nets and the NBA denied that Tsai tried to get Morey fired or that he pushed the NBA to apologize.

Later, after Morey saved his job with help from powerful supporters who championed his right to free speech, the Nets quietly refunded Morey’s purchase of a suite for a Rockets game at Barclays Center. Morey believed Tsai had disinvited him, according to a person who was scheduled to attend. A source close to the Nets said Tsai was unaware of the decision, which was related to concerns about possible protests.

Morey declined comment for this story.

Tsai is hardly the only NBA owner heavily exposed in China.

ESPN employed Strategy Risks, a New York-based firm that quantifies corporate exposure in China, to examine the portfolios of 40 principal NBA owners. Heat owner Micky Arison is chairman of Carnival cruise lines, which has a joint venture with a state-owned Chinese shipbuilder facing U.S. government sanctions. Hornets owner Michael Jordan earns millions through Nike’s China business, which makes up 19% of the company’s revenue. Nuggets owner Stan Kroenke owns Arsenal, the first English Premier League club to establish an office in China, and is a partner there — with state-run China Central Television (CCTV) — on one of the most popular soccer programs in the country.

The investments create an awkward dance in which the NBA, owners and players avoid positions on issues they otherwise embrace in the United States. No owner reflects this tension more than Tsai, for whom more than half of his $8.7 billion net worth is linked to China through Alibaba and his ownership of the Nets, according to Strategy Risks. Since Tsai became an owner, the NBA has expanded a long-standing partnership with Alibaba, allowing fans to view content and purchase gear across the company’s platforms.

To a growing degree, sports is a flashpoint in the U.S.-China conflict. The United States led a diplomatic boycott of the recent Winter Olympics in Beijing — an event some critics dubbed the “genocide games.” In December, the Women’s Tennis Association indefinitely suspended play in China to protest the treatment of Peng Shuai, a player who has rarely been seen in public after accusing a high-ranking Chinese official of sexual assault.

For this story, ESPN, assisted by Strategy Risks, reviewed financial data, human rights reports and China’s state-run media, as well as interviewing current and former NBA employees, human rights monitors, U.S. policymakers, academics and others in the United States, Hong Kong, Taiwan and Mainland China.

A NATURALIZED CANADIAN citizen, Tsai, 58, was born in Taiwan. His parents fled Mainland China in 1948 during the Communist takeover. His father, Paul Tsai, was the first student from Taiwan to earn an elite J.S.D. degree at Yale Law School; Paul Tsai later returned to Taiwan to start a prominent law practice and serve in the Ministry of Economic Affairs. Joe Tsai was sent to the United States at 13, attended a private high school in New Jersey, earned undergraduate and law degrees at Yale and gravitated to a career in private equity. He speaks fluent Mandarin and considers himself Chinese — an ethnic distinction that transcends borders or nationality.

In 1999, Tsai was introduced to Alibaba founder Jack Ma, then working out of a small apartment in the city of Hangzhou. The entrepreneur seemed like a character out of “a Kung Fu novel,” Tsai later recalled, referring to Ma’s charisma. Tsai gave up his $700,000-a-year job to translate Ma’s vision into a legitimate enterprise. Tsai incorporated Alibaba, raised capital and became Ma’s right-hand man and alter ego.

Alibaba developed into the largest ecommerce company in China, with sales surpassing Walmart’s, eventually expanding into logistics, cloud computing, financial services and entertainment. The company’s $25 billion IPO in 2014 was the largest on record at the time. Tsai holds 1.4% of Alibaba’s shares, according to the company’s annual report. He is listed by Forbes as the world’s 254th-richest person.

Over the past two years, Alibaba has come under the growing sway of China’s Communist Party, part of a government effort to exert more control over the country’s tech industry. In 2020, the government abruptly canceled a $37 billion IPO for Ant Group, a financial technology spinoff of Alibaba, after Ma publicly criticized banking regulations.

Alibaba is “effectively state-controlled,” according to a recent study on the company by Garnaut Global, an independent research firm that analyzes the Chinese Communist Party structure and China’s technology footprint.

Under Tsai’s leadership, Alibaba funded companies that helped China build “an intrusive, omnipresent surveillance state that uses emerging technologies to track individuals with greater efficiency,” according to a 2020 congressional report.

Those technologies have been used widely in the western region of Xinjiang, where the government has forced more than 1 million Uyghur Muslims and other ethnic minorities into barbed-wire “re-education” camps, policies that have been described as cultural “genocide” by the United States, several other countries and human rights organizations.

ESPN could find no record of Tsai publicly addressing China’s repressive policies in Xinjiang or Alibaba’s funding of companies whose technology was used by the government in the abuses. But many China experts hold him accountable.

“Joe Tsai has had all the warning in the world about what is happening in Xinjiang, and if he thought it was important to extricate Alibaba, it would have happened,” said Matt Schrader, a China analyst for the International Republican Institute, which promotes democracy around the world. “Joe Tsai is the second-most powerful person at the company.”

On Oct. 7, 2019, the U.S. Department of Commerce announced that 28 Chinese organizations — including Megvii and SenseTime, the Alibaba-funded artificial intelligence companies — had been added to the “Entity List,” which imposes trade restrictions on people or institutions engaged in activity “contrary to the national security or foreign policy interests of the United States.”

In addition to his role as executive vice chairman, Tsai oversaw Alibaba’s investment committee. From 2017 to 2019, Alibaba participated in three major investment rounds for Megvii. In 2018, led by funding from Alibaba, SenseTime raised $620 million, making it the world’s most-valuable AI startup at the time. Alibaba and its affiliated companies currently control 29.4% of Megvii and 7% of SenseTime, according to recent financial documents.

Megvii and SenseTime form half of China’s “AI Dragons,” government-backed companies in the global battle with the United States for artificial intelligence supremacy. The companies promote tools for businesses and the public sector, but their facial recognition technologies have surfaced in connection with China’s ubiquitous surveillance network.

Surveillance is at the core of China’s efforts to control the Uyghur population, a policy the government says is necessary to stop terrorism and maintain stability. ESPN reported in 2020 that American coaches at an NBA training academy in Xinjiang were surveilled and harassed. One coach said he was detained three times, comparing the atmosphere to “World War II Germany.”

The NBA has since ended the academy program, which included two other locations, after an investigation determined “the centers did not meet our NBA standards,” a source familiar with the decision said.

In a 2018 report titled “The Rise of Digital Authoritarianism,” China was identified as the “worst abuser” of internet freedom by Freedom House, a bipartisan nonprofit focused on promoting democracy.

“One of the things that makes [China] distinct is that tech there is designed to meet the standards of government needs,” said Samantha Hoffman, a senior analyst with the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI), an independent research group.

“There is a type of cooperation between companies that is on the face normal but abnormal in a political context,” Hoffman told ESPN.

In 2019, Hoffman’s group issued a series of reports that linked Megvii, SenseTime and other tech firms to the abuses in Xinjiang. Citing Chinese documents and government reports, the research group said Megvii worked in cooperation with security services, including one instance in which its facial recognition software was used to trigger a “Uyghur alarm” that could be sent to police.

SenseTime, the group concluded, relies on the “largesse of the party-state, particularly its investment in two government projects linked to public security surveillance as well as the surveillance state in Xinjiang that have benefited from an estimated $7.2 billion worth of investment in the past two years.”

Also in 2019, The New York Times and Human Rights Watch both reported that Megvii and SenseTime were among companies that built algorithms enabling the government to track the Uyghur population.

Alibaba became “concerned” after Megvii and SenseTime were placed on the Entity List, a source close to Tsai told ESPN. The company made sure it did not hold board seats in the two companies, was not directly involved in operations and was reassured by company executives that they weren’t targeting Uyghurs. Alibaba chose not to divest because of its responsibility to shareholders, according to the source, who described Alibaba as a “passive investor” in Megvii and SenseTime.

Alibaba’s investments took place before the companies were blacklisted, the source emphasized, adding that numerous U.S. investors also hold stakes in Megvii and SenseTime.

IPVM, a surveillance industry research firm, revealed additional evidence about Megvii and SenseTime in 2020 and 2021, and also reported that an Alibaba website included instructions on how to use software to identify Uyghurs.

Alibaba responded that it was “dismayed” and “never intended for the technology to be used in this manner.” The company also said it had “eliminated any ethnic tag on our product offering.” IPVM confirmed the changes.

Matt Turpin, the former China director for the National Security Council, participated in discussions over which companies to add to the Commerce Department blacklist in 2019. Tsai, he said, is “under significant pressure to be seen as doing what Beijing wants him to do. I don’t necessarily fault him. He’s in this impossible position.”

But he said Alibaba’s support of Megvii and SenseTime and human rights abuses were well documented and should give the NBA pause.

“Last I checked, that’s a pretty abysmal thing to be associated with,” Turpin said. “In today’s NBA, I guess it’s not a problem.”

Last December, the U.S. Treasury Department added Megvii, SenseTime and six other Chinese companies to a separate blacklist that prohibits Americans from holding stock in those firms. A department spokesman accused the companies of “actively cooperating with the government’s efforts to repress members of ethnic and religious minority groups.”

Schrader, the China analyst, agreed that Tsai is in a difficult position because of Alibaba’s dependence on the government. But he said Tsai has a choice.

“Joe Tsai could resign,” Schrader said. “He doesn’t have to do this. He’s a Canadian citizen. He has the freedom to make that choice so long as Alibaba continues to facilitate and participate in a genocide.”

TOTING A STACK of highlight reels to present to Chinese television executives, former commissioner David Stern introduced the NBA to the country in the late 1980s. Today, NBA China is valued at $5 billion. (ESPN owns 5% of NBA China.)

Like all foreign companies, the NBA operates in China at the whim of the Communist Party. “It’s not like the U.S., where regulatory bodies issue a warning or sue you, you hire a bunch of lawyers and defend yourself,” said Victor Shih, an expert on China’s corporate economy at University of California, San Diego.

“They can shut you down overnight,” Shih said. “The Chinese Communist Party creates the pressure on businesses and businessmen with a lot of exposure in China. It becomes very difficult for these people to navigate.”

Neither Silver nor anyone from the league office has commented on human rights abuses in China. When the league closed a training academy in Xinjiang two years ago, NBA deputy commissioner Mark Tatum repeatedly declined to say whether the move was related to human rights concerns there.

The NBA is far from unique. Numerous businesses have tried to capitalize on the immense Chinese market, only to be accused of selling out American values. That includes Disney, ESPN’s parent company, which faced criticism from human rights activists after filming part of the 2020 live-action remake of “Mulan” in Xinjiang. Last year, when Disney launched its streaming service in Hong Kong, the company did not include an episode of “The Simpsons” critical of the Chinese government.

Since 2016, ESPN has had a content-sharing partnership with Tencent, the technology giant that streams NBA games in China. After the Morey tweet, the Rockets, then the league’s most popular team in China, disappeared from Tencent. When Morey left Houston to become president of basketball operations in Philadelphia, the 76ers soon followed. Earlier this year, after then-Celtics center Enes Kanter Freedom called China President Xi Jinping a “brutal dictator,” Boston games were taken off Tencent.

Two weeks ago, regular-season NBA games appeared again on CCTV for the first time since the Morey tweet. The government-owned Global Times reported the network would now show fewer games and outside guest commentators no longer would be invited to work the broadcasts.

“The Chinese Communist Party has mastered the art of squeezing, or threatening to squeeze, the interests of elites, like NBA owners and players,” Turpin said. “All of this is a calculated influence campaign that has been underway for years, which uses the self-interest of business, entertainment, academic, political and cultural elites to get them to shape broader public perceptions of the regime in Beijing.”

IN 2018, TSAI purchased a 49% interest in the Nets from Russian billionaire Mikhail Prokhorov. Six months later, Silver announced that Tsai would join the board of NBA China, a separate entity with offices in Beijing and Shanghai.

The following spring, the NBA expanded a partnership with Alibaba to create an “NBA Section” across the company’s platforms; the deal gave Alibaba’s 700 million users one-stop shopping to view NBA highlights and other content and to purchase gear.

That fall, Tsai took full control of the Nets. He paid $2.35 billion, the highest price for a U.S. sports franchise at the time. He also owns the WNBA’s New York Liberty and a professional lacrosse team, and he has stakes in another professional lacrosse team, a lacrosse league, eSports and Major League Soccer’s Los Angeles FC.

“The NBA needed more of a foothold in China, and Alibaba is one of the largest, most powerful companies in that nation,” said Chris Fenton, a businessman who serves on the board of the U.S.-Asia institute and has written extensively about the tradeoffs of doing business in China. “The NBA had to be thinking, ‘Holy cow, if we can get this guy in the league, it would make us awesome in China.'”

Two months after Tsai became sole owner of the Nets, Morey sent his tweet.

A former data analyst at MITRE, the federally funded research and development corporation, Morey had friends involved in the Hong Kong protests, the latest of which had followed a Chinese prohibition on masks to prevent protestors from shielding their identities.

Tsai was preparing to leave for China to attend exhibition games there when Morey tweeted. He was soon contacted by deputy commissioner Mark Tatum, who told him the tweet had provoked significant anger in China. Tsai thought he could play the “middle man,” a source close to him said. He drafted a letter and sent it to Tatum, who oversees international operations. Tsai received no response and posted it on Facebook from his private plane.

Tsai described the message as an “open letter to all NBA fans.” He invoked Chinese history to explain why “the Daryl Morey tweet is so damaging” and vowed to “help the League to move on from this incident.” He indicated that Morey had supported a separatist movement, a bitter point of contention for Morey and his supporters, who saw the protests as a fight for democracy.

As the issue raged on social media in both countries, senior NBA officials braced for China’s response. Silver was in Japan, about to travel to Shanghai; some worried the commissioner might be detained or that the government would shut down the games before tipoff. “We had contingencies for everything,” said a former senior NBA executive in Asia who asked to remain anonymous because the conversations were confidential.

Silver, in his first statement, acknowledged that Morey’s tweet had “deeply offended fans in China and called that “regrettable.” He also noted the league’s support for individuals “sharing their views.”

Even before the controversy, the NBA had begun to consider contingencies in the event a player spoke out about human rights. Inside the Hong Kong office, the tense political climate was creating divisions, and NBA officials worried about safety. The league studied how other foreign companies had saved their businesses by issuing apologies for offending China.

“It was, ‘These are some examples of what other companies have been doing,'” one NBA source familiar with the debate told ESPN. “I don’t think it ever got to the point where it was, ‘This is going to be our position.'”

Suddenly it was reality. To many NBA officials and league executives, the response was obvious: The league would have to fire Morey and issue a public apology.

Morey heard directly from at least one NBA owner that Tsai was pushing to fire him to appease the Chinese. Turpin volunteered to help Morey and quickly became convinced that the Rockets’ general manager was fighting not only the Chinese government but also Tsai.

“My impression of Joe Tsai’s role in this was that it was extremely unhelpful,” Turpin said. “He was laying out to the other owners how completely unacceptable it was that anyone weigh in on Hong Kong. It colored the way the rest of the league lined up against Daryl.”

The Nets strongly denied that Tsai intervened.

“Joe Tsai did not speak to any owners about Mr. Morey after the tweet and it’s absolutely false that he advocated for anything to happen to Morey,” Mandy Gutmann, a Nets spokesperson, wrote in an email. “Only the Rockets make personnel decisions about their team.”

Mike Bass, the NBA’s chief communications officer and executive vice president, said Tsai “never asked or intimated to the league office that Daryl Morey should be fired or that we should apologize.”

Regardless, the NBA’s stated principles were butting up against the realities of doing business in China. “I think the NBA was caught with its feet in two boats, and both were separating,” Fenton said.

In Shanghai, Tsai worried the government would cancel the games, the source close to him said. He asked his Alibaba co-founder, Jack Ma, to contact city officials to let the exhibitions continue. Ma was successful. Meanwhile, LeBron James, whose new movie “Space Jam: A New Legacy,” was in production, raged to players about Morey during a meeting in China at a Ritz-Carlton, according to a source familiar with the meeting. (After returning to the U.S., James said Morey was “misinformed” in his opinion about Hong Kong.)

With the Rockets pushing for an apology and powerful figures like Tsai and James aligned against him, Morey scrambled to save his career. He deleted the tweet soon after it was posted and later tweeted, “I did not intend my tweet to cause any offense to Rockets fans and friends of mine in China. … My tweets are my own and in no way represent the Rockets or the NBA.”

Morey spoke with current and former White House officials, a Democratic governor and others who rallied around him. Turpin worked Congress and the White House to push back.

“I wanted to make it clear to the NBA that there was a broader aspect and costs to the U.S. to being seen as caving in,” Turpin said.

Pottinger, then deputy national security adviser specializing in China, said the White House “knew we had to put a marker down somehow. I remember many of us at the White House saying this is really bad precedent. We don’t want American businesses abandoning values in order to abide by Chinese censorship.”

Pottinger said he spoke directly with then-Vice President Mike Pence, who later addressed the controversy in a speech: “The NBA is acting like a wholly owned subsidiary of that authoritarian regime.”

Republicans and Democrats in Congress rallied behind Morey and railed against the NBA. A bipartisan letter signed by, among others, Sen. Ted Cruz, R-Texas, and Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, D-New York, said it was “outrageous that the NBA has caved to Chinese government demands for contrition.”

Silver issued a second statement, acknowledging his first comments “left people angered, confused or unclear” and affirmed the NBA’s commitment to free expression.

Morey, who believed he’d be forced to resign, stayed with the Rockets for another year before joining the Sixers.

In a recent statement provided to ESPN, Silver said, “We have always supported and will continue to support every member of the NBA family, including Daryl Morey and Enes Freedom, expressing their personal views on social and political issues.”

The NBA declined to make Silver available for an interview.

Shih, the scholar who studies Chinese elites and finance, said the Communist Party essentially has a playbook for events in which China comes under attack: All government workers and major business people are expected to stand with the party.

“So over the years, I’m sure business people like Joe Tsai have learned this expectation,” Shih said. “That’s not like a decree. It’s just over time you learn to say, ‘Oh, everyone’s doing this. When there’s negative publicity event, now I know the norm of what I’m supposed to do.'”

Seven months after the tweet, with little fanfare, the NBA changed leadership in China. With COVID-19 spreading, Derek Chang, who had been CEO for just over a year, resigned to join his family in London. He was replaced by Michael Ma, a Chinese national whose father, Ma Guoli, helped launch China’s first national sports channel, completed the first TV deal with the NBA and went on to become chief operating officer of broadcasting for the 2008 Beijing Olympics.

Shih said the move made sense: “You hire someone like that with a lot of connections, they can call up their friends who are still in government and say, ‘Look, this was purely an accident. What can we do to make it OK for all the different stakeholders?'”

The league said the decision was based on Ma’s qualifications.

“Michael Ma worked at the NBA for more than a decade and helped launch NBA China in 2008 before leaving the NBA in 2016 and ultimately becoming CEO of Endeavor China,” said Bass, the NBA spokesman. “When Derek Chang resigned from his position in May of 2020, Michael’s experience in building and managing global brands, combined with his familiarity with the NBA from his prior decade-plus stint with the league, made him uniquely suited to lead our basketball and business development initiatives in China.”

TWO WEEKS AFTER Tsai’s Facebook post, hundreds of protesters attended a Nets game wearing black “STAND WITH HONG KONG” T-shirts.

The protestors included Nathan Law, a pro-democracy activist who, at 23, won a seat in Hong Kong’s legislature in 2016. At his swearing-in, Law protested the oath of allegiance to China, adding “You can chain me, you can torture me, you can even destroy this body, but you will never imprison my mind.” His seat was revoked; the next year he was briefly jailed. Last spring, he was granted political asylum in England.

Law told ESPN that Tsai has “become like a spokesperson for the Chinese Communist Party, which he is in disguise of.”

“It doesn’t matter if you call him an entrepreneur, a sports owner or a philanthropist, he is channeling the kind of Chinese authoritarianism into the U.S. with a more soft approach that’s quite daunting,” Law said.

Tsai believes much of the criticism he receives is politically motivated by people who purposely distort his views, according to sources close to him. He supports personal freedoms but believes they can get in the way of stability that fosters economic growth and improves people’s lives. He likes to point out that China is still underdeveloped, with a per capita income ($10,435, according to the World Bank) far behind that of the United States ($63,593), and that living outside of poverty is itself a human right.

“It’s a cost-benefit [analysis],” the source said of Tsai’s views. “If you’re running a country of 1.4 billion people, you have to make a tradeoff between everything that’s just free and running amok versus bettering people’s lives over time.”

Like the NBA, Tsai has championed social justice in the United States.

Tsai and his wife, Clara Wu Tsai, have donated hundreds of millions of dollars to social justice initiatives and academia. After George Floyd’s murder, the couple committed $50 million to create the Social Justice Fund, a racial justice and economic recovery initiative in Brooklyn. Last May, Tsai and others raised $250 million in response to hate crimes against Asians during COVID. The Tsais donated thousands of masks and ventilators to New York when the city was the epicenter of the pandemic.

“Fortunately, I came here when I was relatively young, I spent most of my formative years in the United States, so I think I understand Americans,” Tsai said during a 2019 discussion at the University of California, San Diego’s 21st Century China Center. “I’ve involved myself a lot in sports, which is a very big part in America, so I feel quite fortunate in that I can have both perspectives and can be balanced about it.”

Tsai has taken a different view on civil liberties in China. During the 2019 forum in San Diego, he was asked about China’s crackdown on academic freedoms.

“It is what it is,” he responded. “The fact is, China today is a single-party system so there’s going to be restrictions on academic freedoms and freedom of expression. I mean, do people like that? I think most people don’t like it, but I think that’s how the Communist Party needs to control that in order to feel confident about pushing their policies in other areas.

“The single-party system is in place because the elite in China feel that China is still a developing country, and I talked about two broader goals: to make sure that the population is wealthier and doing better and also to restore this sense of renaissance and pride about Chinese culture. They feel that dissent has to take a backseat and whatever they’re doing is right.”

In 2018, during a panel discussion at the Milken Institute, Tsai said stifling democratic freedoms was necessary for China to develop its economy.

“You need to understand that it is important for the Communist government that there’s absolute stability in the country,” Tsai said. “In the American context, we talk about freedom of speech, freedom of press, but in the China context, being able to restrict some of those freedoms is an important element to keep the stability.”

In 2015, Alibaba paid $266 million to buy the South China Morning Post, the most prominent English-language newspaper in Hong Kong. In a letter to readers, Tsai insisted Alibaba wouldn’t compromise the newspaper’s editorial independence but made it clear the paper would provide a perspective on China missing from coverage by the Western media. “We see things differently, we believe things should be presented as they are,” Tsai said in an interview with the paper. He explained that one of the main reasons Alibaba bought the paper was “to tell the biggest story of our lifetime, which is China.”

A 2020 story in The Atlantic, headlined, “A Newsroom At the Edge of Autocracy,” detailed how editors at the paper had recast language in a story about the Hong Kong protests to show protesters in a more negative and aggressive light. The magazine cited sources as saying the changes “exemplified the heavy-handed, slanted editing that became common” at the paper during the demonstrations.

Neither Tsai nor anyone from Alibaba has attempted to shape the paper’s editorial policy, a source close to Tsai said.

Last year, during an interview with CNBC, Tsai defended Hong Kong’s 2020 National Security Law, under which authorities have detained at least 150 pro-democracy activists, academics, lawyers and journalists. The United States and other countries have imposed economic sanctions in response.

Tsai, who lists his business address as Hong Kong and maintains a residence there, pressed his argument during the Morey crisis that the crackdown was necessary to preserve stability and defend China against separatism.

“What is this for? It’s against sedition,” Tsai said. “It’s against people that advocate splitting Hong Kong as a separate country. I want to make sure that we prevent foreign powers from carving up our territories. I think Hong Kong should be seen in that context.”

Tsai’s views on Hong Kong stem from his personal experiences there, said the source close to him. He witnessed “rioters storming the Hong Kong legislature, vandalizing property and defacing the Chinese flag,” the source said. Tsai also was aware of protesters attacking Mandarin speakers, and he felt physically threatened, the source said. Tsai believes that the image of peaceful protestors simply seeking more freedoms is a false narrative created in the West, the source said.

In the CNBC interview, asked to comment on China’s human rights issues, Tsai said, “You have to be specific on what human rights abuse you’re talking about because the China that I see, the large number of the population — I’m talking about 80-90% of the population — are very, very happy for the fact that their lives are improving every year.”

Tsai’s response was widely circulated on Chinese social media, where he was credited with taking a controversial topic and turning it into “positive PR.” Some referred to the interview as Tsai’s “shining moment.”

Tsai’s assertion that the Hong Kong protests are an independence movement is disputed by many activists and China experts who seek to hold China to promises for free elections and assembly, among other rights.

“His hinting that the uprising in Hong Kong is because of foreign powers is completely false,” Law said. “Hong Kong people have their own demands. They want democracy.”

Tsai is convinced that “self-determination for Hong Kong” is part of Law’s “manifesto,” according to a source close to Tsai.

Jerome Cohen, a professor emeritus at New York University School of Law who spent decades representing American companies in China and who was a classmate of Tsai’s father at Yale Law School, said Tsai is presenting a “somewhat distorted picture.”

Cohen said he appeared as part of a series of panel discussions at Yale in 2016, when Tsai donated $30 million and the school’s China Center was renamed to honor his dad. “I thought I’d be mischievous and pointed out that Yale Law School seemed to be a very dangerous place for people from China. I named six or seven scholars, great people who had spent time at Yale Law School, and after leaving they got locked up in China.”

Cohen said Tsai downplayed concerns about “human rights in China” in a subsequent panel.

Cohen said he wasn’t surprised: “I already anticipated what the argument would be from somebody who had just made billions of dollars on the Mainland.”