Senators were largely divided along party lines Wednesday as they debated to what extent Congress should be involved in reforming college sports during a summer when options for college athletes to make money will be expanding.

Starting in July, a series of state laws will make it illegal for schools and the NCAA to punish college athletes in at least a half dozen states for making money by selling the rights to their name, image and likeness (NIL). The NCAA has asked Congress to help by creating a national law that would create a consistent set of rules for athletes and include restrictions designed to make sure college sports remains an amateur endeavor. Republican senators who have been involved in crafting NCAA-related legislation urged their colleagues, during a committee hearing Wednesday, to quickly pass a narrow bill that would address NIL rights prior to state laws going into effect in a few weeks. Democratic counterparts argued that Congress needed to take this opportunity to impose broader reform on the NCAA by mandating an increase in healthcare and educational benefits along with NIL rights for college athletes.

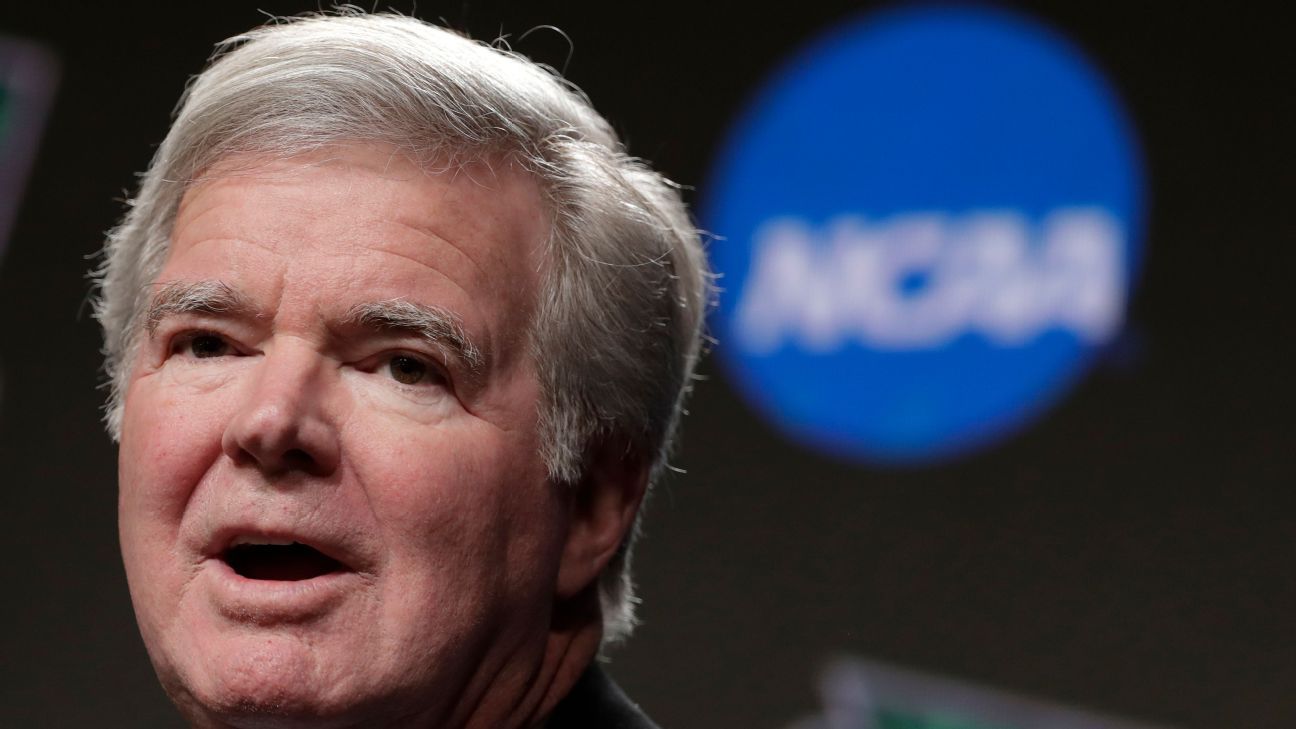

More than a half dozen bills to reform college sports have been proposed in Congress during the past two years. Sen. Maria Cantwell, D-Wash, who chairs the Senate commerce committee, has been working with lawmakers who have put forth those proposals to try to reach a compromise for the past several months. She convened a committee hearing Wednesday, inviting NCAA President Mark Emmert and Gonzaga basketball coach Mark Few, among other college sports stakeholders, to discuss the issue.

Emmert told the senators that the NCAA is hoping to pass its own set of rules in late June that will open up some NIL opportunities for all of its athletes. However, those rules are very likely to be more restrictive than the state laws slated to go into effect next month. Eighteen states have signed laws and, while many of them are similar, they contain a variety of different details and exact start dates. Emmert and his colleagues have asked Congress to create a national rule so that some states don’t have fewer restrictions than others, which would create a recruiting advantage.

“We recruit nationally and internationally,” said Few, who won a national title with the Bulldogs, but is based in a state that does not yet have an NIL law on the books. “To not have the ability to compete on some sort of level playing field with people who can provide monetary gifts or endorsements will put us at a disadvantage we couldn’t make up.”

Sens. Roger Wicker, R-Miss, and Jerry Moran, R-Kan, stressed a sense of urgency to correct that potential imbalance quickly. Both Wicker and Moran have proposed bills that would allow college athletes to monetize their fame through endorsement deals, autograph signings, the hosting of camps and other methods.

Sen. Cory Booker, D-N.J., and some of his fellow party members argued that addressing only NIL issues doesn’t go far enough to correct what they call major injustices in the NCAA’s business model. Booker proposed legislation, last year, that would force the NCAA and its member schools to cover medical costs for sports-related injuries for years after a player’s college career ends, provide lifetime scholarships for athletes who remain in good academic standing, create enforceable penalties for schools that do not follow proper medical protocols and give athletes a bigger voice in advocating for more rights in the future. Booker said he recognizes the urgency but he believes that if broader reforms aren’t imposed now while the NCAA is in need of help, there won’t be an interest in revisiting those issues in a timely manner.

“We cannot trust that this will fix itself,” Booker said. “This is the moment. This is the opportunity. If we delay justice for these athletes, justice delayed is justice denied.”

Emmert and fellow panelist Wayne A.I. Frederick, the president of Howard University, said they were concerned that the burden of paying for additional healthcare costs for athletes might be too much for many lower-income athletic departments to handle. They said it could lead to some of those departments choosing to discontinue some of their sports in order to afford the added costs of caring for the athletes that remain. Cantwell was among multiple people at the hearing who suggested that the NCAA and its bigger-name schools should be willing to help subsidize its fellow members so they can afford to properly care for athletes.

“There is a lot of money in college sports,” she said. “And there’s going to continue to be a lot more money in college sports.”

Emmert said he felt it was certainly “do-able” to find some mechanism for funding those extra expenses for athletes at schools with fewer resources.

Several Congressional aides told ESPN, last month, that it was very unlikely that Congress will pass any type of college sports legislation before July. The debate appeared to be no closer to the finish line during Wednesday’s hearing.

That means there is likely to be some sort of unequal playing field as state laws start to trickle into effect this summer. The NCAA could potentially file lawsuits against each state with a new law in hopes of delaying its implementation. Emmert said that thought had been widely discussed, but he thought it was unlikely that schools would want to go through the complicated process of suing their own state. When pressed to say if those lawsuits were still an option, Emmert declined to provide a definitive answer, saying that decision would have to be made by the NCAA’s Board of Governors.