When the U.S. women’s national team and the U.S. Soccer Federation agreed to a new collective bargaining agreement back in 2017, it seemed like a relief for both sides at the time. The USWNT’s previous contract had expired months prior, and the players had considered going on strike earlier in the process but worried about how it could affect the National Women’s Soccer League, which the USWNT players were obligated to play in. With a CBA finally done, it appeared everyone could move on.

But that’s not really what happened. In 2019, the players sued U.S. Soccer alleging gender discrimination over the compensation and other non-monetary issues — much of what was in the CBA they signed in 2017. The players have maintained that they asked in those negotiations for the same contract the men get, but U.S. Soccer dismissed the idea outright, leaving them with no choice but to accept an unequal contract so they could keep playing. The federation denies that happened, but what’s clear is that the CBA the federation signed for the women in 2017 and remains in effect today is very different from the men’s CBA — and that has been a big problem for U.S. Soccer, both because of the bad publicity it has generated and because of the equal pay lawsuit that is still working its way through the legal system.

With the USWNT’s CBA set to expire on March 31 after agreeing to a three-month extension, and USMNT still operating on a CBA that technically expired on Dec. 31, 2018, both sides are negotiating for new contracts.

Whether the USWNT and the USMNT are willing to accept a joint contract — and it appears for now they are not — it’s clear there are plenty of differences to reconcile to eliminate the large disparities in the current deals. To make the two teams’ contracts more similar, who benefits and who loses out?

Two different contract structures

Every CBA for either team is traditionally built on previous CBAs, and the next ones will be no different. While there are a lot of ways the current contracts between the USWNT and the USMNT are similar, each team prioritized different things when negotiating, resulting in different deals overall.

The USWNT players, for instance, surprised U.S. Soccer negotiators in 2017 when they announced they would take control of the licensing and sponsorship rights that U.S. Soccer had controlled in previous CBAs. The players felt U.S. Soccer wasn’t maximizing their marketability, so the USWNT launched its own commercial arm, signing licensing deals and collecting royalties without U.S. Soccer’s involvement. In the USMNT’s CBA, however, the men continued to let U.S. Soccer sign such deals on the players’ behalf, with the revenue split between the federation and the USMNT.

The men’s CBA also makes no mention of health insurance, unlike the women’s CBA, which guarantees it. The federation often cites this in arguing the women get better perks, but in actuality, the women get health insurance through the U.S. Olympic Committee since the women are considered Olympic athletes and the men aren’t, per FIFA rules. U.S. Soccer only pays the taxes for that health insurance, as stipulated in the CBA, and it’s only worth about $1,500 per year per player.

At the same time, both teams have essentially the same language around hotel accommodations: The teams and the federation produce a shortlist of preferred hotels in given geographic locations, which the federation is supposed to choose from. If the federation doesn’t choose from the list, it “will explain its rationale to the Players Association,” according to the language in both contracts.

The biggest difference between the two contracts — and the one that has caused the most tension — is how the players get paid. Some of the players on the women’s team get salaries, regardless of games played, but no players on the men’s team do.

First, it’s important to understand why this big difference exists. Year-round salaries were first introduced by U.S. Soccer for the USWNT in their 2005 CBA, when women’s national team had very few club options: They faced the choice of playing soccer for their country with no financial stability, or getting other jobs to earn a better living. Working an office job and playing soccer wasn’t feasible: When monthlong tournaments came around, like a World Cup, players usually had to quit their jobs or be fired.

Every USWNT contract since 2005 has been built upon that basic salary structure, but in their last CBA, the USWNT players took a step away from it. The number of players eligible for salaries went down over the life of the contract, while the number of non-salaried players who rely exclusively on call-up fees, roster appearance fees and performance bonuses increased. Salaried players earn $100,000 per year, regardless of playing in games, while non-salaried players earn between $3,250 and $4,500 per game, depending on the year of the contract and the “tier” of the player.

Players on the USMNT, meanwhile, are paid only based on call-ups, game appearances and performance bonuses. A player earns $5,000 for making a game roster, which means that for a typical 23-player roster, U.S. Soccer sets aside $115,000 per game as base pay.

In other words, U.S. Soccer does set aside a guaranteed pot of money for the men, but only if they play games. If not for the USMNT failing to qualify for the 2018 World Cup or the pandemic, the USMNT probably would’ve played more games in 2018 and 2020, which would’ve meant more game-appearance fees and a much higher base pay for the USMNT over those years.

When U.S. Soccer says it has offered the USWNT the same contract structure that the USMNT has — something neither side disputes — it means that it offered to eliminate salaries for the women and provide the per-game fee and bonus structure. But what the USWNT has argued, both in the court of public opinion and in legal filings, is that U.S. Soccer never offered the same dollar amounts for such performance bonuses.

Performance bonus pay gap

Most games that either team plays in a given calendar year have traditionally been friendly games, even in years with a major tournament. The men’s calendar is becoming more congested with the new CONCACAF Nations League on top of the Gold Cup and World Cup qualifying, making less room for friendlies, but the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated that trend by forcing important games to be squeezed into fewer international windows. Due to fewer international tournaments on the women’s calendar, the USWNT plays more friendlies, but either way, friendly bonuses figure to be a major source of income for both teams going forward.

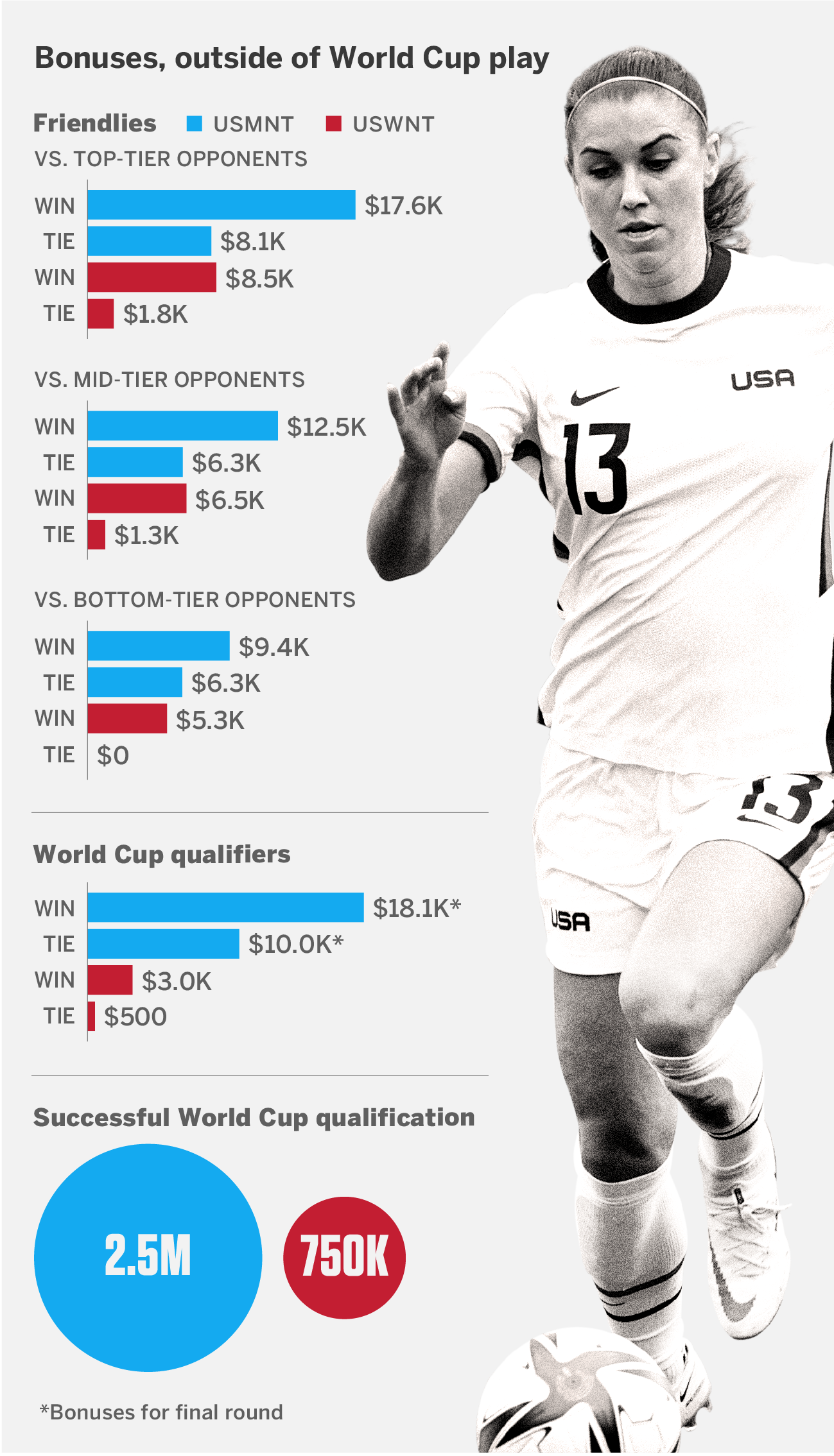

Both teams structure their friendly bonuses in a similar fashion. They each set three tiers of opponents — for the women, the top opponents are ranked 1-4 in FIFA’s world rankings and 1-10 for the men, which reflects the greater number of competitive teams on the men’s side. Mid-tier opponents are 5-8 for the women and 11-25 for the men, with the bottom tier consisting of all teams after that. Both the USMNT and USWNT receive top bonuses for beating their biggest rivals: Canada for the women and Mexico for the men.

The top end and low end of the bonuses are both significantly higher for the men. The highest friendly bonus for the men, $17,625 for beating a top-tier team, is more than double the women’s highest bonus, $8,500 for beating a top-tier team. The men each get a bonus of $6,250 just for tying a bottom-tier team, while the women get $0 for the same thing.

Each team is also entitled to exclusive bonuses because the two teams don’t play in the same tournaments. For instance, the USWNT can earn $500,000 as a team for qualifying for the Olympics, although it doesn’t get any bonuses for winning individual Olympic qualifying games. If it wins a gold medal, that’s worth a $100,000 bonus per player, while silver is $55,000 and bronze is $25,000. Since the senior men’s team doesn’t compete in the Olympics — the men’s tournament is limited to U-23 teams, with three overage exceptions, to avoid conflict with the FIFA World Cup — no such bonuses exist in its contract.

The men do, however, get bonuses for competing in the CONCACAF Gold Cup. Winning games during the tournament can be worth as much as $17,625 per player, and winning the Gold Cup is worth $11,250 per player. The women compete in a CONCACAF Gold Cup, too, but they aren’t entitled to individual game bonuses for the tournament unless it doubles as the qualifying tournament for the World Cup.

The widening World Cup divide

For all the differences in the USWNT and USMNT contracts, the bonuses offered for World Cup performances are where the split becomes the starkest, and it’s no surprise that much of the USWNT’s ongoing equal pay lawsuit focuses on these numbers.

The tone is set during World Cup qualifying, when the men earn $2.5 million as a team for qualifying and the women earn only $750,000 for the same thing. During World Cup qualifiers, the men can earn up to $18,125 per player in the final round for each win, but the women get only $3,000 per player for each win.

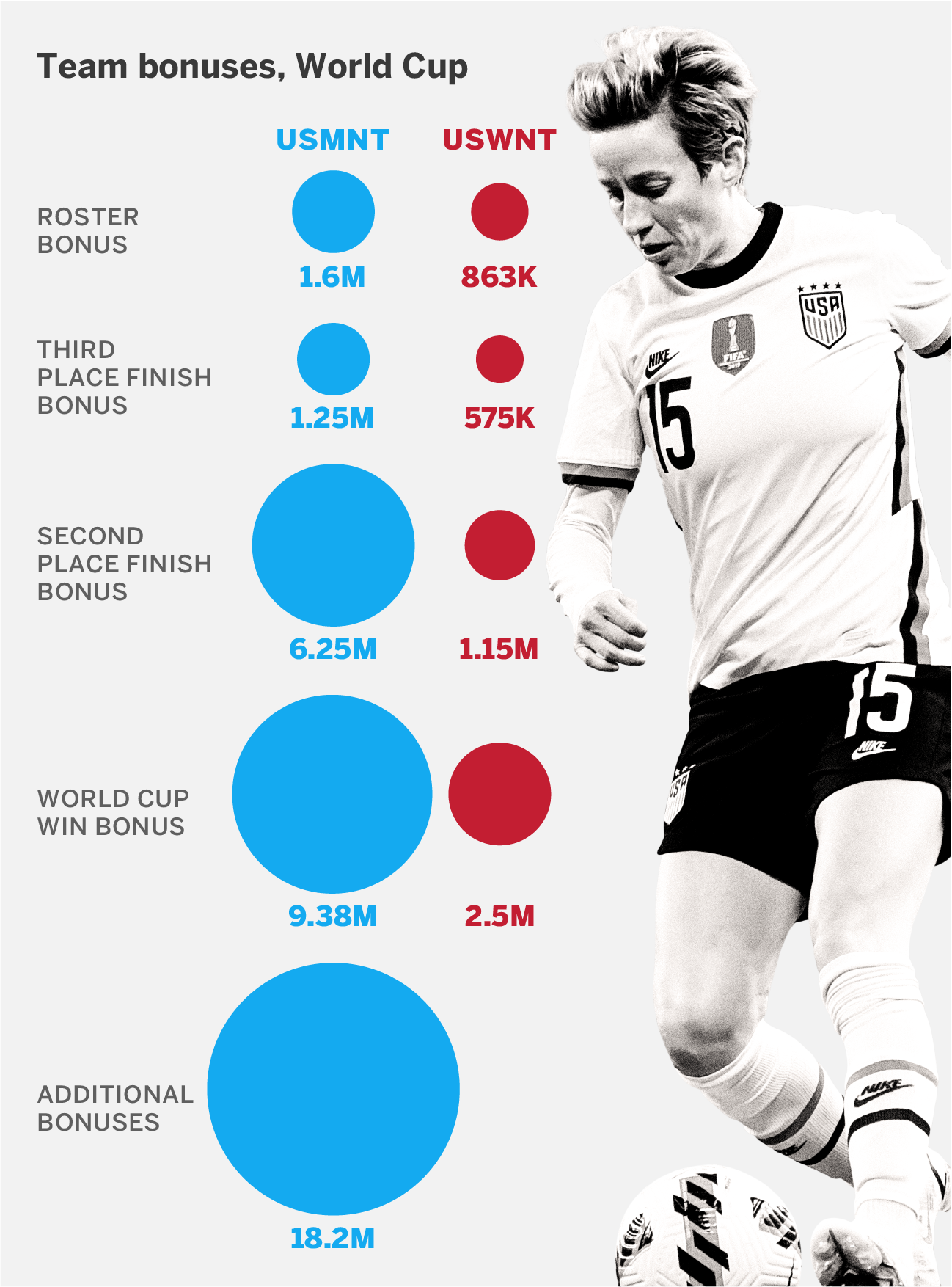

But it’s once the tournament begins when the largest gaps emerge. While the women start cashing in if they finish in third place ($575,000 for the team) and they can share $2.53 million if they win the whole thing, the men collect handsome rewards for every stage of the tournament before the final. Reaching the round of 16 alone is worth $4.5 million for the USMNT, the quarterfinal round is worth $5 million, and the semifinal is $5.625 million. That’s all before the $9.375 million bonus in the USMNT’s contract with U.S. Soccer if they win the World Cup.

It’s impossible to look at World Cup bonuses without examining the prize money from FIFA, the governing body of global soccer and the organizer of World Cups. Even though U.S. Soccer sets its own World Cup bonuses, FIFA prize money looms in the background.

In the last World Cup cycle, FIFA offered a prize of $38 million to the team that won the men’s World Cup in 2018 (France), and just $4 million to the team that won the women’s tournament in 2019 (the USWNT). In all, FIFA offered a total of $400 million for the men’s World Cup and just $30 million for the women’s tournament.

(There is a popular bit of misinformation for why this discrepancy exists: a fake number has circulated claiming that the Women’s World Cup brings in $131 million in revenue for FIFA while the men’s World Cup brings in $6 billion. This is false, and FIFA itself has confirmed it because FIFA sells sponsorships and broadcast rights for all of its World Cup events as a single bundle, making Women’s World Cup revenue unknowable. Why FIFA refuses to offer equal prize money — it has recently widened the gap rather than narrowing it — is unclear, but it’s also irrelevant for the purpose of U.S. Soccer negotiating CBAs with its national teams because U.S. Soccer can’t control that.)

U.S. Soccer likes to blame FIFA for the size of the World Cup bonuses in the USWNT’s contract, but it’s worth noting something important: U.S. Soccer has never opted to base its bonuses for the USWNT or the USMNT directly on FIFA prize money. The bonuses in their current contracts are not a percentage of FIFA’s payouts. Instead, U.S. Soccer has chosen its own bonuses to offer both teams, which sometimes deviate from FIFA’s prize money.

For instance, in U.S. Soccer’s CBA with the USMNT, the men get $218,750 per point won in the group stage of a World Cup, with a maximum payout of $1,968,750. This is a bonus U.S. Soccer concocted — it has no direct correlation to FIFA prize money, which is awarded based on which round of the tournament that teams reach.

Under the current USMNT and USWNT contracts, if FIFA stopped offering prize money for World Cups altogether, the federation would still owe the millions of dollars promised if the teams won. By the same token — and what U.S. Soccer was likely expecting — if FIFA’s prize money drastically increased, U.S. Soccer wouldn’t have to pay all of it out to the teams and could pocket the extra.

This where the probability of each teams’ success at a World Cup comes into play.

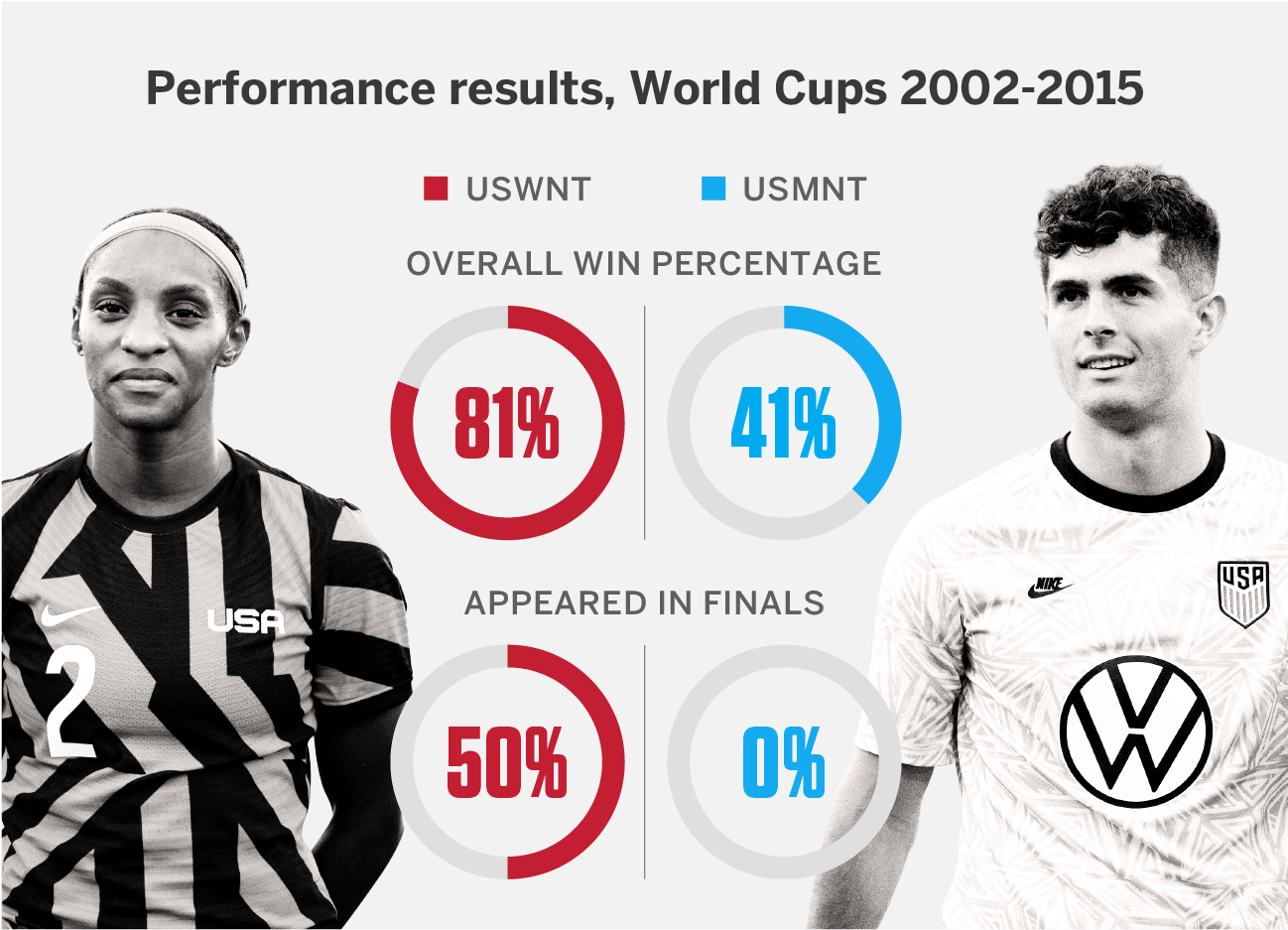

Former U.S. Soccer president Sunil Gulati, on a conference call after the USWNT filed an initial wage discrimination complaint with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission in 2016, was asked whether the women “deserve to be paid equally” to the men’s team. In his answer, he said a lot of factors go into how the players are paid, including “the track record of teams” and “incentives.” By Gulati’s admission, it was easier to offer the men top-end bonuses that U.S. Soccer believed it would probably never have to pay.

Historically, any World Cup bonuses U.S. Soccer offered the men beyond a certain point were as good as Monopoly money — there was almost no chance the men would collect the bonuses. Each team’s record in the four World Cup cycles before the teams negotiated each of their current contracts made that clear, and neither team could’ve predicted it during negotiations, but the men wouldn’t even end up qualifying for the 2018 World Cup.

Capturing the peak of the upside

Performance bonuses can reward players for their on-field success, but what about when on-field success translates into unprecedented commercial success? When the USWNT won the World Cup in 2015, their contract didn’t allow them to reap any extra rewards.

When three-star USWNT jerseys were flying off the shelves, that money didn’t go to the players. When the USWNT set an attendance record for a standalone friendly six weeks after the World Cup, drawing more than 44,000 people to Heinz Field in Pittsburgh, they still got the same small cut of ticket sales. The USWNT was more popular than ever, and U.S. Soccer ended up with a $17 million windfall thanks to it, but the players did not.

“I thought it was bulls—,” then-USWNT defender Meghan Klingenberg later explained. “All these people are making money from our likeness and our faces and our value, but we’re not. We’re only getting money from our winnings, and that doesn’t seem right.”

The USWNT was unable to cash in on the peak of its popularity at the time, and it prompted the team to change two things in its current CBA when it negotiated it in 2017. The first was taking control of the image rights to launch its own licensing program, so players’ names and likenesses could be featured on everything from socks to NFTs with the players getting a cut. The second was the addition of provisions designed to capture the upside of unprecedented growth.

Both the USWNT and the USMNT get $1.50 from each ticket sold for U.S. Soccer-hosted games, but now the USWNT players get boost from brisk sales. After 17,000 tickets are sold, they get an extra 7.5% per average ticket price, and a $15,000 bonus when games sell out. Although U.S. Soccer and Soccer United Marketing are dissolving their partnership next year, SUM has been responsible for selling broadcast rights for national team games, as well as sponsorships for the teams, and the USWNT wanted a cut when SUM performed better than expected, too. That came in the form of a bonus: whenever SUM generated more than $26.5 million in gross revenue each year, the USWNT would get 10% of it.

The USMNT has never concerned itself with capturing that kind of upside because, in part, the USMNT has never experienced an explosion in popularity the same way the USWNT has. But now as the teams work on new contracts that will be more similar than in the past, the question will be: Which parts of each contract should be kept, and which parts shouldn’t? The teams’ current CBAs are the starting point for negotiations and will ultimately help decide what their new CBAs will ultimately look like.

The USWNT has until March 31, the new expiration date on their current CBA, to figure it all out. If not, the CBA will roll over and they will play on an expired contract — but they would no longer be bound by their CBA’s no-strike clause. The men’s team, meanwhile, will continue to play on their years-expired contract until they sign a new deal with the federation and, just as they almost did last year, they can go on strike at any time.